Deep Mapping Estate Archives: An update from Jon Dollery

Deep Mapping Estate Archives: An update from Jon Dollery

Hello there! My name is Jon Dollery. I am the Mapping Officer at the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW). I’ve been working at the Commission for the past 8 years since completing my MA in Landscape Archaeology at the University of Wales, Trinity Saint David. My main day to day job is maintaining and updating the Commission’s in-house Geographic Information System (GIS) software and several spatial datasets that relate to this historic environment of Wales. However, I have just started a new avenue of exciting work and research which I would like to give you and update on.

Along with my RCAHMW colleague Scott Lloyd, I am working on an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded project called ‘Deep Mapping’ Estate Archives: A New Digital Methodology for Analysing Estate Landscapes circa 1500-1930. The work we are looking to undertake could significantly change the way we access historic mapping sources. It may also help us further understand how the landscapes of the past have changed and been altered into the landscapes of the present. The AHRC has provided £249,538 in funding to the project which is being led by the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates (ISWE) at Bangor University, in partnership with Aberystwyth University, RCAHMW, National Library of Wales and North East Wales Archives. The project is centred on 6 historic parishes situated across Flintshire and Denbighshire border: Llanferres, Llanarmon-yn-Iâl, Llandegla, Mold, Nercwys and Treuddyn. This area was specifically chosen as it gives a good topographic balance (consisting of upland common land, lowland agriculture, and the urban setting of Mold town) as well as having a good number of estates. The project started in September 2020, pandemic not withstanding, and over the past several months we have been busily working away.

The Commission’s role in the project is to bring together several historic mapping sources together into a GIS environment. The first step in the process is identifying the historic maps that we need. There are 4 types of historic maps that we have identified as being critical:

- Ordnance Survey (OS) 1st Edition 25 inch to the mile (1:2,500) county series map sheets. These maps where the first ‘total’ survey of Britain that was undertaken by the Ordnance Survey between 1850 and 1890. These maps have an astonishing amount of topographical detail and will serve as the base-mapping for the project.

- Tithe Maps (1830’s-1860’s). These maps where produced under the Tithe Communion Act 1836 which meant that all fields within each parish in Wales and England where surveyed and their value established to calculate the amount of tithe to be paid by the landowner to the church. These maps are again an invaluable asset as they not only detail the landscape of rural areas in the mid-19th century, but also include information such as land use, landownership, acreage, value etc. Effectively generating a snapshot of the landscape, both topographic as well as ownership.

- Enclosure Maps are a fascinating source. Although there are enclosure maps dating from 1595 onwards, many were produced in the late 18th and early 19th century.

- Estate Maps.

Scott Lloyd has spent some time tracking down these maps. This is not an easy task as many of these maps are not held in one central location but rather are held in several archives such as the National Library of Wales and local record offices. Fortunately for some of the map sources, previous projects such as the National Libraries Cynefin project had digitised all of the Tithe maps and have made them available online. The real challenge was sourcing the OS County Series maps. Although our project area is relatively small area, there are at least 50 map sheets that cover this area, all of which are spread between various archives in mid and north Wales. Normally this would be a challenge, then add to that the restrictions of the pandemic of 2020 – it has been a small miracle that Scott was able to arrange for the transportation, digitisation and return of these sources within a short period of time. The maps were transported from the local record offices to the National Library of Wales whose dedicated team of digitisation specialists were able to make high resolution scans of the maps.

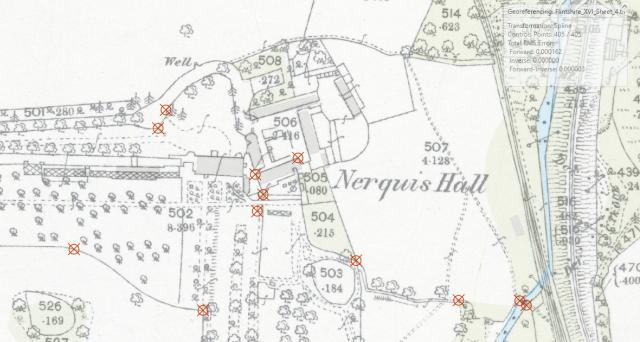

After obtaining the digitised scans of the maps, we are now able to import them into GIS software. This is where my expertise comes into the project. This is done using a process called georeferencing. This works by taking a digital copy of the historic map and using control points we can add a point to the map. Usually, we would choose the corner of a field boundary or a building. If the point we have chosen still exists today on the modern map, we can then fix the point from the historic map to the point on the modern map. The more control points we use will then fit the historic map spatially to the modern map. Since receiving the digital scans of the OS County Series Maps from the National Library, I have been able to georeference all 50 sheets. We have not yet georeferenced any of the other historic mapping sources to date as our focus for the first stage of the project is centred around the OS County Series maps.

Georeferencing

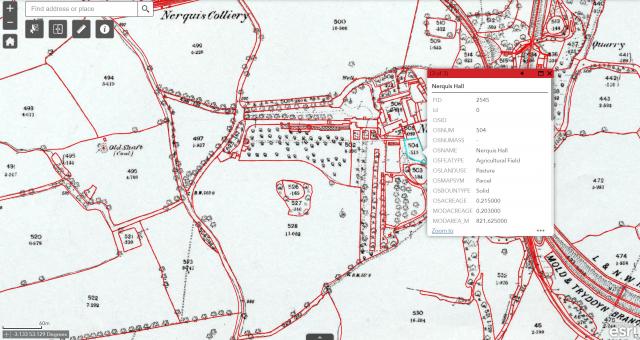

Although having a digital georeferenced image of our historic maps makes them accessible digitally, the project aims to go much further by making the maps more usable by undertaking a process called ‘polygonization’. This effectively means that we create a vector dataset within the GIS that recreates all the features on the map. So, each map feature: field, parcel, building, trackway, road etc. is given its own polygon. The benefit of doing this is that behind the polygon, we can link it to a database, or what we refer to in GIS terms as an ‘attribute table’. Within the attribute table we can add as much information as we like by creating data columns. Each column records a specific data type, such as field name, land use, ownership, acreage etc. This means that all the ancillary information contained within the maps or with associated sources such as books of reference can be added directly to the dataset. This means that a user will be able to click on the polygon of, let’s say a field, and will be presented with all the attributes associated with that particular field.

Attributes

Since September I have been focusing on one township within the project area: Nercwys. After georeferencing the six OS County Series sheets that cover the township the next step was to undertake the polygonization process. To do this, I take a copy of a modern vector dataset to use as a base dataset: Ordnance Survey’s MasterMap topographic layer. OS MasterMap records every fixed feature within the UK and is a continuous digital map which is regularly updated by the OS. I strip out all of the attributes from this modern dataset and replace them with the template structure for the attributes we need to record in relation to the OS County Series. Then I overlay this modern vector dataset with the digital georeferenced OS County Series map. I then manually edit each polygon to reflect the boundaries of each feature from the OS County Series map. In most cases there has not been any change to the landscape features. However, in some cases where there is change, this can be rectified by either splitting the modern polygons or merging two or three polygons into a single polygon.

Polygonization – Before & After

Once we have completed creating the polygons to reflect the OS County Series the next step is to add the attribute information. This is done by Scott, who goes through each polygon and enters the information recorded on both the map and other external sources such as the Books of Reference. This can be a slow process but once the information is entered, it means we can do much more spatial interrogation and cross referencing of the data as well as make it more visual. This stage also acts as a natural checking point in which the polygons that I have created can be checked to make sure that no mistakes have occurred.

The last exciting thing that I have managed to complete since September is the georeferencing and polygonization of the Mold Town Plan. While the OS were surveying the County Series maps in the 19th century, they produced further detailed maps at a scale of 10.56 feet to the mile (1:500) for the main towns of Wales and England. The town plan for Mold was surveyed in 1871 and consists of six sheets and contains an astonishing amount of detail. Again, following the process I described for the OS County Series maps, I imported the maps, georeferenced them and then polygonised them using modern OS MasterMap as a base dataset. Scott then entered the attribute information for each polygon generated for the town plan. The results being that we have created a digital vector dataset that has all of the information from the original map, but is in a format that we can manipulate to make it more user friendly. One example of what we have been able to do with this dataset is to take the symbology from a colourised map sheet and apply it to the entirety of the dataset. This means that we can colourise map sheets that where never colourized or at least no colourized copy exists today. If we were just concerned with digitising and georeferencing the images, there would be a mismatch with some areas colourized, while others would be black and white. The benefit of this methodology allows us to standardise symbology across the entirety of the dataset.

Town Plan – B&W & Town Plan – Colourized

Although we are at the early stages of the project we have managed to formulate and standardise our methodology for bringing these historical maps to life. The next step is to continue working our way through the OS County Series sheets for the project area. Once we have achieved this, the next step will then be to incorporate the other, older mapping sources such as the Tithe, Enclosure, and estate mapping. Then we will look at other records to see if we can use place name and other geospatial information to create ‘map’ layers from these textual sources.

The ethos of this project is do once, reuse many times. I can’t help feeling that all of the information we are recording from these historic maps will have some bearing upon the modern world. This information is not only useful for the historic environment sector but could have some use for other sectors such as local and national government, academia, utilities not to mention the private sector. Not forgetting of course, the general public. This methodology will substantially open these maps for public use and consumption. It will aid further research both academic and personal. Although we are looking at a very small area, there is potential that in future, a similar project could look at doing this on a larger scale, perhaps for a county or even for all of Wales. Although one can only dream about the potential held in these sources, in the meantime there is plenty of polygonization and georeferencing left to do. So please do watch this space.

Publication date: 13 April 2021