The mass influx of this fresh water into the Atlantic has already been established as a potential climate tipping point- described as a point at which an irreversible shift happens within one of the earth’s systems on which we rely.

With this in mind, oceanographers at Bangor University are leading a transatlantic team of researchers working to better understand how that freshwater will affect short-term weather patterns and to improve the models which predict future climate and to reflect the possible changes to ocean layering, circulation and northwards ocean heat transport within the Atlantic.

Yueng-Djern Lenn, Professor of Physical Oceanography at Bangor University is leading the Natural Environment Research Council-funded research project.

She explains,

The Arctic is the biggest reservoir of freshwater on the planet. Currently, circulation patterns are holding most of the freshwater within the Arctic’s Beaufort Gyre. The question is what happens when there is a rapid freshwater release from the seas into the ocean.

Because freshwater is lighter than salty seawater, it has the potential to change the ways in which different layers of water mix. This in turn can affect both the movement of ocean currents and the circulation and transport of layers of warmer and colder waters deep within the oceans. These are so vast that they can influence the jet stream, and as a result, our weather systems.

“Freshwater is doubtless already reaching the Atlantic, and in some cases, contributing to a shift in the Atlantic storm track towards the UK, but we don’t fully know how the release of larger freshwater amounts will affect ice-ocean-atmosphere feedbacks in the Arctic and North Atlantic circulation. Will the whole system be able to absorb the water and adjust, or will it happen so quickly that it changes the current circulation patterns, and will we see the repercussions of that? I would suggest the latter is most likely, given the weather we’ve seen in the last few years.

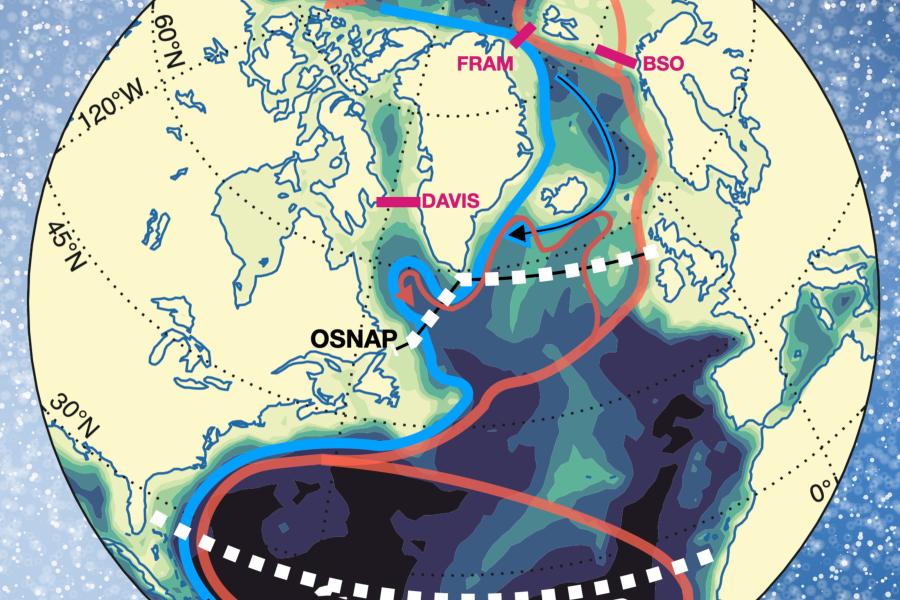

Lenn’s team at Bangor University are experts in both Arctic waters and ocean mixing. Their role will be to analyse data collected from a network of buoys and profiling floats which are collecting data at strategic points across the Atlantic, building on a theory developed by her predecessor at the School of Ocean Sciences, Prof John Simpson. The team will use the data to compare against and improve state of the art computer simulation/ model held at Texas University. Colleagues at the University of Exeter and National Oceanography Center will draw out the weather and climate predictions.