Prehistoric communities off the coast of Britain embraced rising seas- what this means for today's island nations

L St. Michael’s Mount, a tidal island off Cornwall, also said to be near the legendary land of Lyonesse.: @benjaminelliott via https://unsplash.com/photos/sg7zgMb3OQYegend has it that the land of Lyonesse was engulfed by the sea in a single night during a dreadful storm. They say that this beautiful land, now lost to the seas, lay somewhere between Brittany and Cornwall, much like today’s Isles of Scilly. The weave between legendary narrative and truth has always been challenging to unpick. In this case, the stories of Lyonesse and rising sea levels in south-west Britain are inseparably intertwined.

St. Michael’s Mount, a tidal island off Cornwall, also said to be near the legendary land of Lyonesse.: @benjaminelliott via https://unsplash.com/photos/sg7zgMb3OQYegend has it that the land of Lyonesse was engulfed by the sea in a single night during a dreadful storm. They say that this beautiful land, now lost to the seas, lay somewhere between Brittany and Cornwall, much like today’s Isles of Scilly. The weave between legendary narrative and truth has always been challenging to unpick. In this case, the stories of Lyonesse and rising sea levels in south-west Britain are inseparably intertwined.

The legend of Lyonesse predates even King Arthur. It was the land of Tristan (who famously loved Iseult), son of noble King Rivalin, whose adventures were chronicled by Thomas of Britain, over 800 years ago. Now underwater, it is rumoured that fragments of masonry from Lyonesse litter the hauls of Cornish fishermen today:

Back to the sunset bound of Lyonesse –

A land of old upheaven from the abyss

By fire, to sink into the abyss again;

Where fragments of forgotten peoples dwealt …Idylls of the King, Alfred Lord Tennyson (1859)

Back then, like now, the coastlines were being submerged by rising seas. If the poets are to be believed, this submergence was in the forefront of people’s minds.

Yet the story of rising sea levels in south-west Britain, and of the prehistoric island communities that it affected, starts many millennia before the legends of Tristan and Arthur. Our newly published research sheds new light on the history of this corner of Britain and could explain how the legendary land of Lyonesse was lost to the seas. This research, which we carried out with an international team, used environmental data to reconstruct past sea levels and the wider landscape and archaeological data to explore the response of the island population to rising seas.

The findings from our research provide a stark (and timely) reminder of the effects sea-level rise can have on coastlines and communities. Importantly, we show that response plans must be designed with both local environments and local cultures in mind.

The Isles of Scilly

In the south-west corner of Britain, beyond Land’s End, lie the Isles of Scilly – a beautiful, low-lying archipelago made up of over 50 islands and rocky islets. Surrounded by the English Channel, they are fewer than 50 km off the coast of Cornwall and host a population of a little over 2,000 people today. Scilly, now a popular tourist destination, is famed for its remarkable range of historic sites. Visitors have abundant opportunities for touring prehistoric monuments and heritage sites, as well as for island hopping and wildlife spotting.

Submerged prehistoric field boundaries, Isles of Scilly. : © Historic England ArchiveThe fragmented islands are separated by shallow, turquoise seas, fringed by white sandy beaches, unusual for coastal locations at this latitude. When kayaking the clear waters between the islets, it’s possible to see long straight rock formations. These are not naturally formed – they are actually submerged stone walls and boundaries from times past, a reminder of the Scilly’s tumultuous relationship with sea-level rise.

Submerged prehistoric field boundaries, Isles of Scilly. : © Historic England ArchiveThe fragmented islands are separated by shallow, turquoise seas, fringed by white sandy beaches, unusual for coastal locations at this latitude. When kayaking the clear waters between the islets, it’s possible to see long straight rock formations. These are not naturally formed – they are actually submerged stone walls and boundaries from times past, a reminder of the Scilly’s tumultuous relationship with sea-level rise.

Rates of sea-level rise in the region are higher than anywhere else on the British Isles. As is the case across Britain (and indeed worldwide), sea-level rise will impact coastal communities on Scilly through increased flooding and coastal erosion caused by more frequent extreme water levels.

It should be unsurprising, then, to hear that the Isles of Scilly have not always looked as they do now. Our recently published data provides new insight into past sea levels, vegetation, and population changes on the islands for the past 12,000 years. The data allowed our team to develop maps of coastline changes, revealing unexpected relationships between sea-level rise, coastal change and the associated human response.

We found that major coastal flooding did not necessarily coincide with the highest rates of sea-level rise. One might expect such flooding to be followed swiftly by abandonment, but instead, we found that the population of the time embraced cultural and behavioural changes. Communities appeared to adapt modes of subsistence in a response to the coastal changes that were underway. It’s clear that the ability to successfully respond to rising seas was centred around culture - being able and prepared to change behaviour. The importance of culture therefore must be recognised in the adaptation plans of today.

From island to archipelago

During the end of the last ice age, when south-east Britain was still connected to continental Europe, Scilly was not an island at all, but was joined to mainland Cornwall by a land bridge.

Sea level around the world rose rapidly with the retreat of the major ice sheets in northern Europe and North America, following the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (around 21,000 years ago), the most recent period when global ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

During this time, the earliest modern humans were able to voyage across Europe with the last of the large ice-age mammals (woolly rhinos, mammoths and cave lions), unencumbered by expansive seaways. By 12,000 years ago, the Isles of Scilly were disconnected from mainland Britain by a seaway. One single large island, nearly 140 km² in size, it was getting rapidly smaller, engulfed by rising seas.

We explored 12,000 years of past sea level and environmental changes, focusing on the Isles of Scilly as a groups of islands that have undergone expansive transformation due to flooding and coastal change. A sea-level reconstruction was developed from fossilised and submerged peat and salt-marsh deposits, which contained evidence of past sea levels from the microorganisms that inhabited the sediments. We used this record to recreate coastline changes, along with reconstructing the vegetation cover of the landscape as well as the population dynamics across Scilly and the wider region.

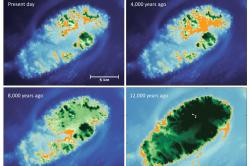

The Isles of Scilly – then and now. Showing land (green), water (blue, darker for deeper water) and the intertidal zone (orange).Relative sea level around Scilly was rising fast 12,000 years ago, a response to the melting of both local and far-field ice sheets. During the Last Glacial Maximum, a large ice sheet occupied Scotland, Ireland and much of northern Britain. When this melted, the land it occupied started to rebound – a great mass of ice had been lifted. This caused the land in the south to sink as the Earth’s crust flexed back to its original position. This process is still ongoing today – the land in south-west Britain is currently sinking by around 1 mm each year (mm/yr) while Scotland continues to rise.

The Isles of Scilly – then and now. Showing land (green), water (blue, darker for deeper water) and the intertidal zone (orange).Relative sea level around Scilly was rising fast 12,000 years ago, a response to the melting of both local and far-field ice sheets. During the Last Glacial Maximum, a large ice sheet occupied Scotland, Ireland and much of northern Britain. When this melted, the land it occupied started to rebound – a great mass of ice had been lifted. This caused the land in the south to sink as the Earth’s crust flexed back to its original position. This process is still ongoing today – the land in south-west Britain is currently sinking by around 1 mm each year (mm/yr) while Scotland continues to rise.

We found that a high rate of relative sea-level rise (nearly 3 mm/yr) continued around Scilly up until 4,000 years ago. At this point, the rate slowed down. Only the ice sheets over Greenland and Antarctica remained, and land subsidence in south-west Britain was lessening. Already, the one large island of Scilly had diminished in size, having lost 100 km² of land to the sea over the 8,000 years up until then.

But the island was still transforming. We found that even though the rate of relative sea-level rise decreased between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago (from nearly 3 mm/yr to less than 1 mm/yr), the land was still being inundated by the sea. This is because the coastline was low-lying, with much of the land area that remained only a few metres above sea level. As the sea level continued to rise, even at the modest rate of 1 mm/yr, dramatic coastal changes were taking place.

Land area was being lost at a rate of around 10,000 m² each year, equivalent to the area of a large international rugby stadium. About half of the lost land was turning into intertidal regions - the area of coastline which is intermittently flooded and exposed during the rising and falling of the tide. In fact, between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago, the amount of intertidal area across Scilly nearly doubled.

Despite this large-scale coastal reorganisation of Scilly, the formation of widespread intertidal habitats means that the changes may not have been entirely negative for coastal communities.

Adapt and overcome

So were humans present on Scilly at this time? Hard archaeological evidence of permanent settlement is not fully apparent until after 4,500 years ago. But our new 12,000 year-long record of environmental change on Scilly reveals that oak woodland across Scilly was evident from 9,000 years ago, but abruptly vanishes 2,000 years later (7,000 years ago), which might suggest Mesolithic humans were clearing forest for hunting and resources. During the Neolithic (6,000 to 4,500 years ago), there is archaeological evidence of island visitors on Scilly from flint microliths, land disturbance and the arrival of grazing animals by the Late Neolithic.

Our research adds to the growing body of evidence for a permanent human presence on Scilly shortly after 4,500 years ago, right at the end of the Neolithic and at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age. It also tells us that during this time of rising seas, the available living space was being flooded and widespread coastal reorganisation was taking place year after year.

Research from other parts of the world (such as the Yangtze in east China) has shown how some Neolithic communities have been forced to flee sites of coastal inundation. It might be tempting, therefore, to think that the Neolithic population on Scilly was likewise compelled to relocate or even abandon the islands. Instead, after 4,500 years ago, there appears to have been an acceleration in human activity, evident from today’s remaining archaeological sites, in particular the Early Bronze Age monuments.

The beginning of the Bronze Age in Britain was heralded 4,500 years ago. On Scilly, the Bronze Age is marked by an incredible abundance of material culture in the form of worked flints, pottery and vessels. Even more remarkable was the density of archaeological monuments. There are over 600 Bronze Age cairns, standing stones, entrance graves and other monuments across Scilly (not including some that may have been lost to the sea), which by then was a landmass of less than 30 km². Archaeology on Scilly during the Bronze Age is richer than at any other period through time.

There was clearly a powerful drive for Bronze Age communities to remain on Scilly. This desire or need to stay is despite a backdrop of rising seas and rate of coastal change that would have been noticeable and impactful across human lifetimes. It suggests that cultural adaption, rather than physical flight, was the preferred solution for the inhabitants of the Isle of Scilly during this time.

We might never know why they remained. But it is likely that the development of expansive intertidal habitats offered opportunities for foraging, fishing and wildfowl hunting. Provided that the island inhabitants of the time were prepared to adapt the way they found food, these valuable food sources could have helped support growing human populations.

Evidence of land disturbance from the pollen and fire records, as well as the archaeological finds across the islands, show that local populations actively managed the landscape. Crops were being grown and animals were being kept. By adapting behaviours and exploiting new intertidal resources (such as collecting shellfish and other edibles), it is possible that the shrinking islands were able to support growing populations.

This demonstrates that rapid sea-level rise does not lead to uniform environmental change or a predictable human response. On Scilly, despite the changing coastlines, coastal communities seem to have flourished by adapting their behaviours. This highlights the importance of centring culture and society in discussions of coastal (and indeed wider climate change) adaptation.

Since the Bronze Age, both the amount of intertidal area and land area of Scilly has continued to dwindle. After millennia of modest rates of rise (around 1 mm/yr), sea levels around the Isles of Scilly are now rising rapidly once more, in line with rates of global mean sea-level rise.

This begs the question, what can we learn from the past, to protect our future?

Unprecedented sea-level rise

Many island nations are already adapting to – or fleeing from – the effects of climate change, including rising sea levels. Thousands of inhabitants of Pacific Islands such as Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Fiji and the Marshall Islands, have relocated to New Zealand for example, leaving their native islands, cultures and associated heritage.

The most recent estimate of global mean sea-level rise – the average rate by which sea level is rising across the entire globe – is 3.6 mm/yr. This is based on the average rate of rise between 2006 and 2015.

Perhaps this doesn’t sound like much. To put it into context, this rate of global sea-level rise is unprecedented for at least 2,500 years. It’s true (as many climate change deniers profess) that in the deep past (during the Pliocene, from 5.3 to 2.5 million years ago, for example) the Earth was warmer and the seas higher than at present. But what is so remarkable about present-day sea level is the exceptional rate of global sea-level rise that we’re currently experiencing.

Even more concerning for many coastal communities is the fact that sea level is not actually level: changes are unique for each point in the world. Melting ice sheets, warming oceans, and alterations to the Earth’s crust are among the processes which contribute to these complex patterns of change. In different places, these processes can either reduce the effects of global mean sea-level rise or exacerbate it.

As ice sheets melt, the world’s oceans rise, but not uniformly. The oceans near melting ice sheets actually fall in level, because ice sheets exert a gravitational pull on the water surrounding it, and the pull diminishes as ice sheets lose mass. Conversely, this results in above-average sea-level rise in far-field regions, such as the tropics.

Global mean sea-level rise is an important concept. It tells us that the current overall rate of rise is unprecedented and alarming. Most important to coastal communities, though, is the rate of local sea-level rise: the change in sea level relative to their coast. It is the patterns of local change that will determine how quickly sea level will rise in a certain location and that threatens, costs, and overwhelms coastal communities.

Resistance and resilience

Today’s coastal regions are densely populated, with an estimated 10% of the global population (around 600 million people) living fewer than 10 metres above sea level. Many huge cities around the world are highly vulnerable to sea-level rise, including Miami (US), Kolkata and Mumbai (India), Alexandria (Egypt) and Guangzhou (China). Millions of people are already facing the immediate threat of rising seas.

And the places that will be hit worst aren’t always obvious: the case of Scilly illustrates this. The most drastic coastal flooding did not happen in response to the most rapid sea-level rise; it happened when a relatively slow rise inundated low-lying land. We must look not only to the places experiencing the highest rates of sea-level rise, but also to those low-lying areas undergoing dramatic coastal reorganisation resulting from a relatively small rise.

The research shows that rates of sea-level change, the reorganisation of the coastline, and the response of the local communities are all highly variable (and, potentially, unexpected) through time. In principle, the potential response options for modern communities to sea-level rise are equally variable. Options include hard engineering solutions, such as the defences built in Tokyo to keep flood waters out, or land reclamation – building seaward to reclaim land from rising waters.

In some instances, rising sea levels can be accommodated, for example by raising houses or diverting roads, or natural approaches can be employed, such as sand dune or mangrove restoration projects. And there persists an ever-increasing importance for well-designed early response systems and evacuation zones in response to the increased severity of storm surges.

Retreat – moving exposed people away from coastal flood zones – is the ultimate adaptation option. Theoretically, the above measures have the potential to be highly effective. But the reality is that the options available to small, often poor, coastal communities are far fewer.

Of course, the best thing to do would be to slow down the rate of global mean sea-level rise, which is a direct result of climate change. Until that becomes a reality, the next best way to protect the culture and heritage of island nations from further rising seas is to adapt. But at what cost? Rising oceans are, unfortunately, unavoidable and inevitable.

The right response is difficult to define. How do we measure the loss of languages and cultures? How a given community feels about migration is complex, driven by multiple individual, social, cultural, economic and political factors in addition to the environment. Understanding the societal and cultural perspectives of coastal populations will be critical for responding successfully to future sea-level rise. If it’s not feasible or realistic to adapt, then what does the future really hold for today’s native islanders?

It is perhaps unlikely that rising seas in the future will result in new intertidal landforms and resources capable of supporting growing populations, as may have been the case on the Isles of Scilly thousands of years ago. But the development of new wetland areas (for example, by allowing vegetated intertidal zones to progress inland as the seas rise) will be absolutely vital for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem health, as well as for generating natural and cost-effective storm-defence systems.

More important is how local communities are woven into physical adaptation strategies. We must respect and protect coastal communities, cultures and heritage sites. Modern coastal communities are demonstrating incredible resistance and resilience to climate-driven relocation. These communities show us that societal and cultural perspectives are at the very heart of the response to rising sea levels, and our research indicates that this has been the case for millennia.

These societal and cultural perspectives will be critical for developing holistic and successful adaptive responses to climate change. Frontline coastal communities need to be heard.

Publication date: 5 November 2020