New research reveals that climate change could disrupt the beneficial relationship between two important coastal species: seagrass and oysters. The findings, published in the Journal of Ecology, shed light on how these species work together to grow and thrive under normal conditions but may struggle as ocean temperatures rise and acidity increases.

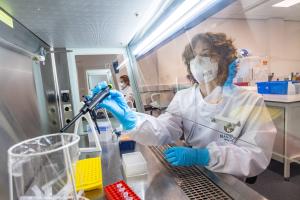

The study, conducted by a team of international marine scientists, explored the interactions between seagrass and oysters in a controlled experiment. By simulating warmer and more acidic ocean conditions, they observed the effects on both species. Under normal conditions, the study found that oysters significantly boost seagrass growth, increasing both leaf growth and plant size by about 30%, whilst seagrass helps oysters by improving shell growth. In other words, oysters use more energy to grow their shells when seagrass is around.

However, when the water became warmer and more acidic, the relationship between the seagrass and oysters became less predictable, indicating that future ocean conditions could disrupt their beneficial relationship. Despite this, one clear benefit under future ocean climates of warmer and more acidic conditions persisted: seagrass improved oyster body condition by 36%, reversing the negative effect of warming and acidification on oyster body condition.

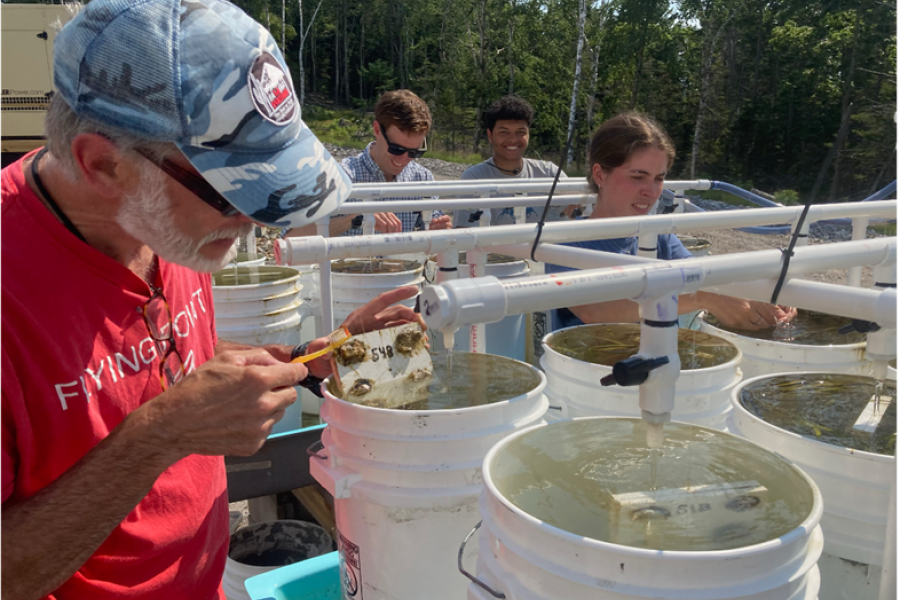

Dr Katie DuBois is a marine ecology lecturer at Bangor University’s School of Ocean Sciences, and co-author of the paper based on research she conducted during her tenure at Bowdoin College, USA. Now continuing her academic career at Bangor, she is set to pursue further research in the same field.

Dr DuBois, explained, “This study highlights the importance of species interactions in understanding ecological responses to climate change. It's not just the individual effects of warming and acidification on seagrass and oysters that matter, but also how their relationship evolves. This knowledge is vital for the conservation and management of coastal ecosystems. By understanding these complex relationships, we can better preserve and protect our coastal ecosystems.

“These findings are particularly relevant for restoration projects and aquaculture, where it's essential to consider how environmental changes impact species interactions. This understanding will aid in developing strategies to support the resilience and productivity of these key species.”