Researchers are confident they have identified the wreck site of HMS Stephen Furness, sunk in 1917 along with over 100 of her crew, after over a century at the bottom of the Irish Sea thanks to the Towards a National Collection project Unpath’d Waters which combines expertise from 25 organisations from across the UK led by Historic England.

Towards a National Collection, an £18.9m investment from the UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) has been set up to connect separate collections, dissolving barriers and unifying data in a digital ‘hyper network’ across the UK’s museums, galleries, libraries and archives.

Its Unpath’d Waters project adopted new approaches to investigate shipwreck sites and a team from Bangor University's School of Ocean Sciences believe they have finally identified the possible remains of HMS Stephen Furness, missing since December 1917 after being torpedoed with the loss of over 100 lives. This discovery has only been made possible by combining existing documentary resources with new scientific datasets identified and accessed by project researchers thanks to innovative digital techniques.

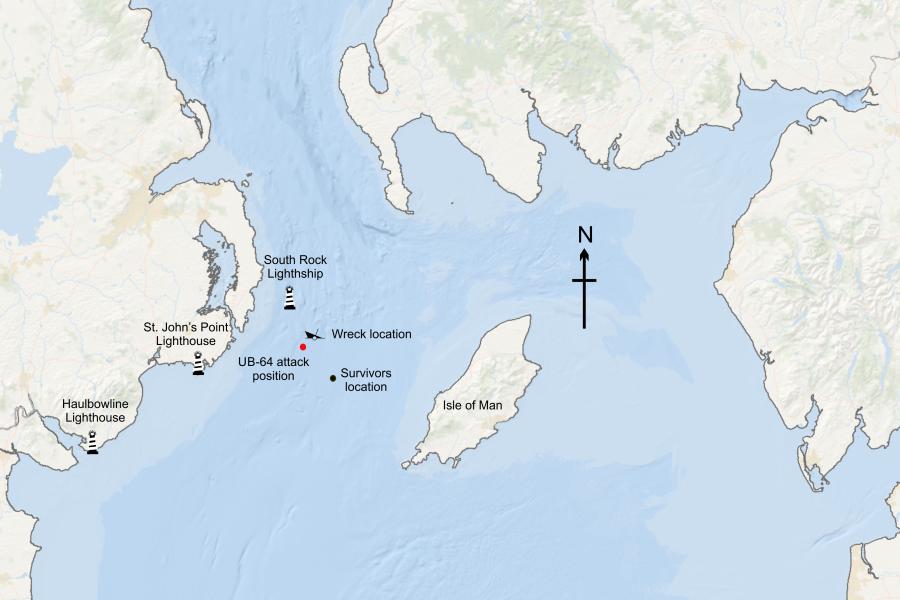

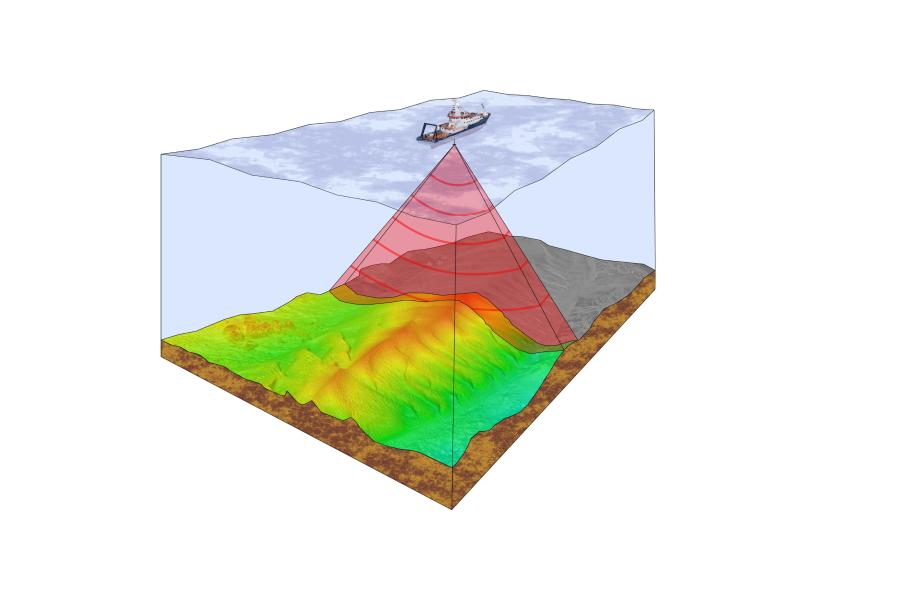

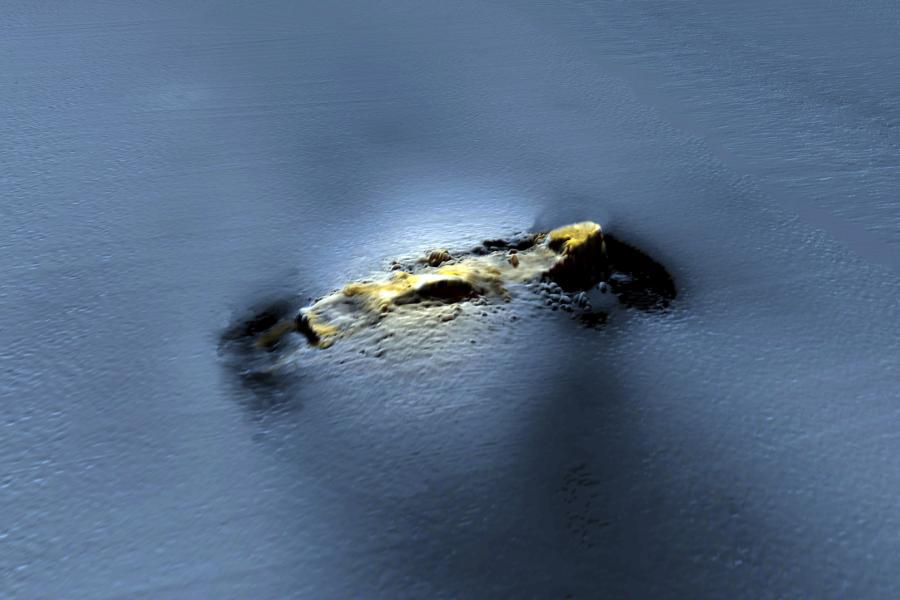

The team analysed high-resolution multibeam sonar data collected by Bangor University’s research vessel Prince Madog to examine the dimensions of all known wreck sites in the region. Combining this information with other resources, including an account of an attack position contained in a U-boat Kriegstagebuch (war diary), meant that identifying the likely resting place of HMS Stephen Furness and several other vessels became a comparatively straightforward exercise, one that could easily be replicated elsewhere.

The wreck in question lies at a depth of ninety meters, approximately ten miles east of the entrance to Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland and was previously considered to be the remains of a Swedish cargo vessel, the SS Maja, torpedoed with the loss of nine lives, exactly a month before the war ended. The research team also believe that they have located the SS Maja’s remains lying a few miles further south. Piecing together all the evidence and information in the various collections has allowed the research team to not only identify the likely resting place of the ship following the attack but also reconstruct some tragic aspects of what followed. The Unpath’d Waters project team have notified relevant authorities of the potential discovery to ensure the wreck is protected.

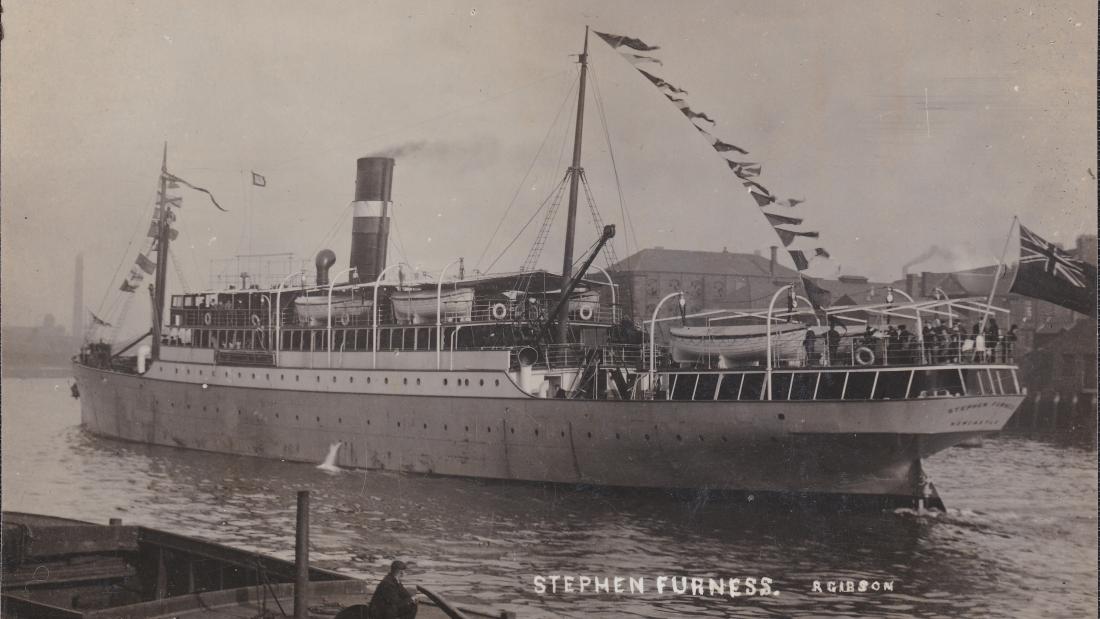

On the afternoon of December 13th, 1917, HMS Stephen Furness was in the northern Irish Sea heading for repairs in Liverpool, when it was struck by a single torpedo fired from UB-64, which had been patiently stalking the Irish Sea for an opportunity such as this for several days. The impact from the torpedo resulted in a boiler explosion causing the 88m long vessel to sink within three minutes. Only twelve sailors from a crew of over one hundred survived. Since that fateful day, until now, the location of the attack and final resting place of HMS Stephen Furness has remained a mystery.

When the team took a closer look at the events that unfolded that day and its aftermath, other unexpected outcomes began to emerge. Sadly, about a month after the sinking, four of the crew who lost their lives during the attack were washed up along the coast of North Wales almost a hundred miles to the south. To better understand how this happened and examine what might happen in other similar scenarios, the team successfully incorporated archived Meteorological Office wind data from the time of the sinking into a tidal model to observe the pathways and timing floating objects would have followed in the Irish Sea given the conditions at the time. The results demonstrated the value and potential that meteorological records and hindcast models may have for identifying more precise locations for missing vessels when the only positional information available is survivors’ and rescue accounts, often provided after being adrift for many hours.

New information from this discovery will enable researchers to explore beyond simple narratives of blockade and U-Boat war, and engage directly with the people involved, the lives they led, and the sacrifices they made. The ship was a converted merchant steamer that may have been used as part of the distant blockade in the Northern North Sea. This blockade was a key component of the Royal Navy’s strategy to curtail German activity and had a significant impact on supplies of food and other essentials in Germany. In the blockade, ships like HMS Stephen Furness were part of day-to-day naval activity that contributed significantly to the direct denial of sea space to German shipping.

Sir Roly Keating, Chair of the Steering Committee, Towards a National Collection, and CEO of the British Library, said, “It’s exciting to see such a tangible example of what happens when disparate historic collections and datasets are brought together in pursuit of new knowledge and scientific innovation. That’s exactly the vision at the heart of Towards a National Collection. All too often, through lack of investment in digitisation, skills and common infrastructure, the UK’s collections have remained fragmented and, in many cases, hard to access, even for dedicated researchers. But their untapped potential – for society, innovation and economic growth – is colossal.”

Dr Mike Roberts, Research & Development Manager at Bangor University’s School of Ocean Sciences, said, “Overall, the research highlights our significant lack of understanding as to what most shipwrecks in UK waters actually represent, which is also a problem at the global scale. However, this project clearly demonstrates the incredible potential our disparate and different collections of information and material have when adopting a collective multidisciplinary approach.”

Phoebe Wild, Research Officer at Bangor University, said, “The multibeam data is what clinched it for us; the data showed that the British position was inaccurate and allowed us to validate the German position. The sonar data was also key for refuting that this wreck was the remains of SS Maja, furthering our case that it is in fact the remains of HMS Stephen Furness. This investigation really illustrates one of the goals of the Unpath’d Waters project - to demonstrate the potential of UK maritime collections."

Professor Christopher Smith, executive chair of the Arts and Humanities Research Council, said, “This is a thrilling discovery and a testament to the power AHRC aims to unleash by connecting the disparate collections of information and material held by the UK’s various heritage institutions through the Towards a National Collection programme. The exemplary work of the Unpath’d Waters project has revealed, at long last, the potential resting place of over a hundred men who died under tragic circumstances and gives us a tantalising hint at the historical riches concealed within the waters that surround us. If the work of Towards a National Collection is already leading to finds this exciting, I cannot wait to see what else it might enable in the future.”

Barney Sloane, Historic England, Principal Investigator, Unpath'd Waters: Marine and Maritime Collections in the UK, said “The likely identification of HMS Stephen Furness is a brilliant and moving example of the potential of the UK’s maritime heritage data and a testimony to the Unpath’d Waters’ team’s collaboration and excellent detective work. The UK’s maritime heritage is incredibly rich, and our project aimed to explore how we can access, link and search this heritage in new ways to create new knowledge and stories. This result is a remarkable example of just how important such an endeavor will prove to be.”

Rebecca Bailey, Programme Director, Towards a National Collection, said, “This remarkable discovery demonstrates what can be achieved when cultural heritage organisations come together to push forwards the development of an inclusive, unified, accessible, interoperable and sustainable UK digital collection. Towards a National Collection is about connecting and opening access to UK heritage – for everyone, not just academic researchers. We want to dissolve the barriers between people, collections and research – big and small, scientific and cultural, national and regional.

“The four sailors that washed up on the coast of North Wales provided an opportunity to use innovative scientific analysis to inform our theory about the wreck. However, it is important to look at the bigger picture here; no matter where the wreck of HMS Stephen Furness ended up, these were four men out of over a hundred that lost their lives when the ship sank. It is easy to get wrapped up in the excitement of searching for a lost shipwreck, but it is also important to remember the human tragedy that is inextricably linked.”