Brambles are considered a nuisance by many woodland managers. But we’ve discovered that fallow deer have a surprising taste for it. In our recent research, we found this unexpected preference by analysing plant DNA from fallow deer poo, offering a fascinating glimpse into their diet. And this discovery could help us better understand how deer shape woodland ecosystems and influence conservation efforts.

Historically, UK deer populations declined because of overhunting, but today, hunting is more of a hobby than a necessity. As people continue shaping landscapes into urban-agriculture-woodland “mosaics”, we have created ideal habitats for deer, providing ample food and shelter, and reduced hunting pressure. As a result, our deer populations are thriving.

The UK government has set a target of net zero carbon emissions by 2050, with tree planting playing a crucial role. But growing saplings past knee height is challenging when deer are grazing nearby. If trees can’t grow, they can’t store carbon.

Fallow deer (Dama dama) are a well-loved species often seen in UK parks. As “intermediate grazers” they eat large quantities of fibrous plant materials, such as grasses, with leafy greens when it suits them.

Studies shows that fallow are one of the least fussy deer species on the planet – they eat just about anything. They also form large social groups. So you can imagine how they thrive in a human-transformed mosaic landscape and the amount of damage they can inflict on woodlands.

Our recent study examined the diet of fallow deer in the Elwy Valley, north Wales. These deer came from a captive herd on a large estate, released when the fences were removed during the first world war. Over the past century, the population has grown from a few dozen to several thousand, raising serious concerns among woodland managers.

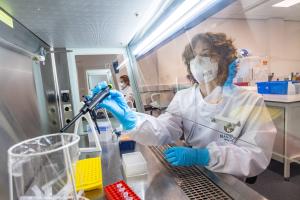

We used a new DNA sequencing technique called “metabarcoding” to reveal what plant species were in around 350 fallow deer poo samples. These were collected from three woodlands in the Elwy Valley every month for two years.

We also surveyed the woodland vegetation to discover how the deer diet related to the seasonal availability of different plants. The nearby Welsh Mountain Zoo kindly provided poo samples from their fallow deer herd to check against our results from the wild deer.

We expected deer to eat plenty of grass all year round and more broadleaf plants in winter and early spring. But the DNA results surprised us. Fallow deer consumed significant amounts of bramble (Rubus fruticosus agg).

Bramble made up 80% of their winter diet, dropping to 50% by late summer. The deer ingested more broadleaf trees in spring and summer while they were in leaf, and consumed large quantities of acorns in autumn. Grasses accounted for only a small portion of their diet, peaking at a mere 6% during the autumn months.

Our woodland vegetation survey had indicated that bramble was the most prevalent plant in the environment. With edible shoots available throughout the year, bramble provides a consistent food source, probably playing a crucial role in the winter diet when other food is scarce.

Consequences for deer, woodlands and net zero

A recent report showed that Britain’s woodland canopies are becoming more open because of severe storms and the spread of tree diseases. This benefits bramble, which can grow back after deer browsing and rapidly colonise woodlands where gaps in the canopy allow more light to reach the ground. But the relationship between bramble, deer feasting and tree regeneration is complex.

Bramble can protect young trees from deer by forming a spiny barrier, but it can also smother saplings and shade out rare woodland plants. In contrast, heavy deer browsing can suppress bramble growth, preventing it from out-competing other vegetation. As deer populations continue to grow while we try to plant more trees and conserve woodland habitats, balancing these factors becomes a problem with no simple solution.

Through plant DNA analysis of deer faeces and stomach contents, we can gain valuable insights for woodland management by discovering what deer are eating across seasons in different habitats. We can also compare the diets of different deer species (we have six in the UK). This approach helps us build a more comprehensive understanding of the ecological role of deer in our woodlands.

For woodland managers, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Simply culling deer may not achieve the desired outcomes. Instead, we recommend examining what is happening to the bramble, tree saplings and other plants in both light and shady parts of the woodland, along with the effects of deer grazing. Adaptive management – tailored to specific site conditions – is central to achieving long-term woodland health and successful tree regeneration.![]()

Amy Gresham, Postdoctoral Research Associate on the iDeer Project, University of Reading; Graeme Shannon, Senior Lecturer in Zoology, Bangor University, and John Healey, Professor of Forest Sciences, Bangor University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.