Celebrated 'English' poet Edward Thomas was one of Wales' finest writers

![]() This article by Andrew Webb, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article by Andrew Webb, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Shortly after 7am on April 9 1917, 39-year-old writer Edward Thomas was killed by a shell during the Battle of Arras in northern France. He left a body of mostly unpublished work that has since cemented his place as one of Britain’s greatest poets.

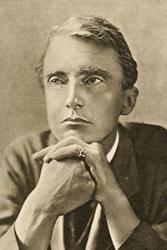

Edward Thomas used English to write about the spirit of Wales.: Arthur St John Adcock/WikimediaAll of Thomas’s 144 poems were written in the two and a half years leading up to his death. Almost immediately on its posthumous publication, his poetry came to speak for a rural England whose surviving people and culture had been decimated by four years of war. In a foreword to the 1920 Collected Poems, Walter de la Mare described Thomas’s poetry as “a mirror of England”, suggesting that it offered readers a portrayal of a rural nation that had been “shattered” by the catastrophic experience of World War I.

Edward Thomas used English to write about the spirit of Wales.: Arthur St John Adcock/WikimediaAll of Thomas’s 144 poems were written in the two and a half years leading up to his death. Almost immediately on its posthumous publication, his poetry came to speak for a rural England whose surviving people and culture had been decimated by four years of war. In a foreword to the 1920 Collected Poems, Walter de la Mare described Thomas’s poetry as “a mirror of England”, suggesting that it offered readers a portrayal of a rural nation that had been “shattered” by the catastrophic experience of World War I.

Thomas has become one of the most widely read English language poets of the 20th century. His Collected Poems has gone through numerous editions, and poems such as “Adlestrop” and “Old Man” have been widely anthologised.

Thomas has a deserved reputation as a poet with an unparalleled eye for the details of the natural world, managing through these observations to make some profound reflections on the human and environmental cost of war. His influence on subsequent generations of English poets is hard to overstate: former poet laureate Ted Hughes famously called Thomas “the father of us all”.

There has been plenty of discussion of Thomas’s work over the past few decades and yet there is one major aspect that has remained largely unexamined: his association with Wales.

An English poet?

Calling Thomas an English poet belies his own complex national identity. Born in London to Welsh parents in 1878, Thomas made frequent trips back to Swansea and the Carmarthenshire areas of south Wales to stay with relatives. He had strong friendships with Welsh-language poets Watcyn Wyn and John Jenkins (“Gwili”), and later attended Lincoln College, Oxford from 1897 to 1900, where he was tutored by Owen M. Edwards, one of the most significant figures in nonconformist Welsh culture.

Edwards awakened Thomas’s sense of Welsh national identity – after graduating he asked his former tutor “to suggest any kind of work … to help you and the Welsh cause”. Three years earlier, Edwards had called for “a literature that will be English in language and Welsh in spirit”, and it seems that Thomas took up his challenge, declaring that: “in English I might do something by writing of Wales”.

Welsh in spirit

Edward Thomas on 1905: WikipediaThe visits to Gwili and Watcyn Wyn became more frequent and both poets feature in Thomas’s 1905 travel book Beautiful Wales. A description of Gwili fishing in a Carmarthenshire stream also features in one of three books of Wales-oriented sketches and short stories published by Thomas between 1902 and 1911: Horae Solitariae, Rest and Unrest, and Light and Twilight. These books are full of Welsh subject matter, including sketches, as well as adaptations of, and allusions to, Welsh folk material and literature.

Edward Thomas on 1905: WikipediaThe visits to Gwili and Watcyn Wyn became more frequent and both poets feature in Thomas’s 1905 travel book Beautiful Wales. A description of Gwili fishing in a Carmarthenshire stream also features in one of three books of Wales-oriented sketches and short stories published by Thomas between 1902 and 1911: Horae Solitariae, Rest and Unrest, and Light and Twilight. These books are full of Welsh subject matter, including sketches, as well as adaptations of, and allusions to, Welsh folk material and literature.

In his review work for newspapers, Thomas lamented the lack of a widely circulated collection of Welsh folk tales, something that he himself put right in 1911 when he published Celtic Stories, an anthology of Welsh and Irish folk stories written “when Wales and Ireland were entirely independent of England”.

While Thomas’s reputation as a quintessentially English writer rests largely on his poetry, it is now clear that even this is not as English as we previously thought. Welsh subject matter clearly creeps into some of his poems. The following verse from Words is a riddle-like reference to the tradition of Welsh bardic poetry:

Make me content

With some sweetness

From Wales

Whose nightingales

Have no wings…

The lines below from Roads allude to Sarn Helen, the mythical Roman road linking fortresses in the north and south of Wales:

Helen of the roads,

The mountain ways of Wales

And the Mabinogion tales,

Is one of the true gods

Recently, however, we have realised that Thomas’s knowledge of Welsh-language poetic metres influenced his work too. Thomas’s poetry has long been regarded as innovative, but critics have tended to look for its origins in his relationship with American poet Robert Frost, the Imagism movement, or in the spoken voice.

What we have missed is the formal crossover between Welsh-language literary forms and Thomas’s use of intricate sound patterns. The opening lines of “Head and Bottle”, for example, repeat the consonant sounds of “l”, “s” and “m” across the first line, and again in the second line. There is also the internal rhyme in “sun”, “sum” and “hum”:

The downs will lose the sun, white alyssum

Lose the bees’ hum

This is a clear example of cynghanedd, the intricate system of consonantal repetition and internal rhyme which is unique to Welsh-language poems.

Thomas certainly was one of the greatest English-language poets but, one hundred years on, it is becoming clear that he belongs just as much to an Anglophone Welsh literary tradition as he does to the literature of England.

Publication date: 7 April 2017