How operational deployment affects soldiers' children

![]() This article by Leanne K Simpson, PhD Candidate, School of Psychology | Institute for the Psychology of Elite Performance, Bangor University was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article by Leanne K Simpson, PhD Candidate, School of Psychology | Institute for the Psychology of Elite Performance, Bangor University was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

So many of us have seen delightful videos of friends and family welcoming their loved ones home from an operational tour of duty. The moment they are reunited is heartwarming, full of joy and tears – but, for military personnel who were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan post 9/11, their time away came with unprecedented levels of stress for their whole family.

Military personnel faced longer and more numerous deployments, with short intervals in between. The impact of operational deployments on military personnel’s mental health is well reported. Far less is known, however, about how deployment affects military families, particularly those with young children.

Military families are often considered the “force behind the forces”, boosting soldiers’ morale and effectiveness during operational deployment. But this supportive role can come at a price.

Research has shown that deployments which last less than a total of 13 months in a three-year period will not harm military marriages. In fact, divorce rates are similar to the general population during service – although these marriages are more fragile when a partner exits the “military bubble”.

But studies have also found that children of service personnel have significantly more mental health problems – including anxiety and depression – than their civilian counterparts. Mental health issues are also particularly high among military spouses raising young children alone during deployment.

Military children

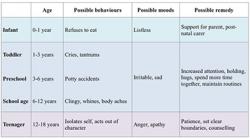

Possible negative changes in child behaviour resulting from deployment.Our understanding of how younger children cope with deployment often stems from mothers’ retrospective reports, or from the children themselves when they become adolescents. Very little is known about the impact of deployment on young children who are at the greatest risk of social and emotional adjustment problems.

Possible negative changes in child behaviour resulting from deployment.Our understanding of how younger children cope with deployment often stems from mothers’ retrospective reports, or from the children themselves when they become adolescents. Very little is known about the impact of deployment on young children who are at the greatest risk of social and emotional adjustment problems.

Unsurprisingly, the studies that have been conducted indicate that it is the currently deployed and post-deployed families that experience problematic family functioning.

A new study that I have co-authored with Dr Rachel Pye – soon to be published in Military Medicine – examines how UK military families with young children function during three of the five stages described in the “emotional cycle of deployment”, when their father is or has recently been on a tour of duty.

The emotional cycle of an extended deployment – six months or longer – consists of five distinct stages: pre-deployment, deployment, sustainment, re-deployment, and post-deployment. Each stage comes with its own emotional challenges for family members. The cycle can be painful to deal with, but those who know what to expect from each stage are more likely to maintain good mental health.

Strength in rules

Our research has found that all military families, regardless of deployment stage, have significantly more rules and structured routines than non-military families. Usually this would be indicative of poor family functioning – as it is associated with resistance to change – but we suggest that rigidity may actually be a strength for military families. It gives stability to an often uncertain way of life.

The findings also support previous research with similar US military families where a parent had been deployed. These families were highly resilient, with high levels of well-being, low levels of depression and high levels of positive parenting.

We used a unique way of examining the impact of deployment on young children. Each of the participants was asked to draw their family so that we could measure their perception of family functioning.

Example drawings from children whose fathers were either currently deployed, about to deploy or had recently returned from combat operations. : Leanne K SimpsonPictures drawn by children of fathers who had returned from deployment within the last six months were quite distinctive. The father was often drawn larger and more detailed than other family members. But in the pictures drawn by children whose fathers were currently deployed, the father was often not included, or the child used less detail or colour.

Example drawings from children whose fathers were either currently deployed, about to deploy or had recently returned from combat operations. : Leanne K SimpsonPictures drawn by children of fathers who had returned from deployment within the last six months were quite distinctive. The father was often drawn larger and more detailed than other family members. But in the pictures drawn by children whose fathers were currently deployed, the father was often not included, or the child used less detail or colour.

When the pictures were re-analysed ignoring the physical distance between the child and parents – which is often used as an indicator of emotional distance, but could for this sample represent a real physical distance – the differences in how the fathers were drawn was still evident.

What all this means is that children who had a father return from deployment within the previous six months, or a father who was currently deployed, were part of the poorest-functioning families in our study.

This may seem like a negative result but our research also indicated that the effect is temporary. The children’s drawings showed differences between the currently deployed and the post-deployed families, but military children without a deployed parent scored similarly to non-military children.

So although military families are negatively affected by deployment, the impact doesn’t last. The vast majority successfully adapt to each stage of deployment.

Like any family, military families do experience problems – but this research highlights the robust, stoic nature of military families and their incredible ability to bounce back from adversity, demonstrating that they truly are the “force behind the forces”.

Publication date: 23 June 2017