Lab-grown mini brains: we can't dismiss the possibility that they could one day outsmart us

![]() This article by Guillaume Thierry, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the School of Psychology is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article by Guillaume Thierry, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the School of Psychology is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The cutting-edge method of growing clusters of cells that organise themselves into mini versions of human brains in the lab is gathering more and more attention. These “brain organoids”, made from stem cells, offer unparalleled insights into the human brain, which is notoriously difficult to study.

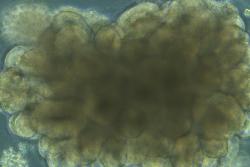

Human cerebral organoids range in size from a poppy seed to a small pea. : Image from NIH Image Gallery via FlickrBut some researchers are worried that a form of consciousness might arise in such mini-brains, which are sometimes transplanted into animals. They could at least be sentient to the extent of experiencing pain and suffering from being trapped. If this is true – and before we consider how likely it is – it is absolutely clear in my mind that we must exert a supreme level of caution when considering this issue.

Human cerebral organoids range in size from a poppy seed to a small pea. : Image from NIH Image Gallery via FlickrBut some researchers are worried that a form of consciousness might arise in such mini-brains, which are sometimes transplanted into animals. They could at least be sentient to the extent of experiencing pain and suffering from being trapped. If this is true – and before we consider how likely it is – it is absolutely clear in my mind that we must exert a supreme level of caution when considering this issue.

Brain organoids are currently very simple compared to human brains and can’t be conscious in the same way. Due to a lack of blood supply, they do not reach sizes larger than around five or six millimetres. That said, they have been found to produce brain waves that are similar to those in premature babies. A study has showed they can also grow neural networks that respond to light.

There are also signs that such organoids can link up with other organs and receptors in animals. That means that they not only have a prospect of becoming sentient, they also have the potential to communicate with the external world, by collecting sensory information. Perhaps they can one day actually respond through sound devices or digital output.

As a cognitive neuroscientist, I am happy to conceive that an organoid maintained alive for a long time, with a constant supply of life-essential nutrients, could eventually become sentient and maybe even fully conscious.

Time to panic?

This isn’t the first time biological science has thrown up ethical questions. Gender reassignment shocked many in the past, but, whatever your beliefs and moral convictions, sex change narrowly concerns the individual undergoing the procedure, with limited or no biological impact on their entourage and descendants.

Genetic manipulation of embryos, in contrast, raised alert levels to hot red, given the very high likelihood of genetic modifications being heritable and potentially changing the genetic make up of the population down the line. This is why successful operations of this kind conducted by Chinese scientist He Jianku raised very strong objections worldwide.

But creating mini brains inside animals, or even worse, within an artificial biological environment, should send us all frantically panicking. In my opinion, the ethical implications go well beyond determining whether we may be creating a suffering individual. If we are creating a brain – however small –– we are creating a system with a capacity to process information and, down the line, given enough time and input, potentially the ability to think.

Some form of consciousness is ubiquitous in the animal world, and we, as humans, are obviously on top of the scale of complexity. While we don’t know exactly what consciousness is, we still worry that human-designed AI may develop some form of it. But thought and emotions are likely to be emergent properties of our neurons organised into networks through development, and it is much more likely it could arise in an organoid than in a robot. This may be a primitive form of consciousness or even a full blown version of it, provided it receives input from the external world and finds ways to interact with it.

In theory, mini-brains could be grown forever in a laboratory – whether it is legal or not – increasing in complexity and power for as long as their life-support system can provide them with oxygen and vital nutrients. This is the case for the cancer cells of a woman called Henrietta Lacks, which are alive more than 60 years after her death and multiplying today in hundreds of thousands of labs throughout the world.

Disembodied super intelligence?

But if brains are cultivated in the laboratory in such conditions, without time limit, could they ever develop a form of consciousness that surpasses human capacity? As I see it, why not?

And if they did, would we be able to tell? What if such a new form of mind decided to keep us, humans, in the dark about their existence – be it only to secure enough time to take control of their life-support system and ensure that they are safe?

When I was an adolescent, I often had scary dreams of the world being taken over by a giant computer network. I still have that worry today, and it has partly become true. But the scare of a biological super-brain taking over is now much greater in my mind. Keep in mind that such new organism would not have to worry about their body becoming old and dying, because they would not have a body.

This may sound like the first lines of a bad science fiction plot, but I don’t see reasons to dismiss these ideas as forever unrealistic.

The point is that we have to remain vigilant, especially given that this could all happen without us noticing. You just have to consider how difficult it is to assess whether someone is lying when testifying in court to realise that we will not have an easy task trying to work out the hidden thoughts of a lab grown mini-brain.

Slowing the research down by controlling organoid size and life span, or widely agreeing a moratorium before we reach a point of no return, would make good sense. But unfortunately, the growing ubiquity of biological labs and equipment will make enforcement incredibly difficult – as we’ve seen with genetic embryo editing.

It would be an understatement to say that I share the worries of some of my colleagues working in the field of cellular medicine. The toughest question that we can ask regarding these mesmerising possibilities, and which also applies to genetic manipulations of embryos, is: can we even stop this?

Publication date: 25 October 2019