Longest-living animal gives up ocean climate secrets

Analysis of the quahog clam reveals how the oceans affected the climate over the past 1000 years

A study of the longest-living animal on Earth, the quahog clam, has provided researchers with an unprecedented insight into the history of the oceans.

The research team showed that prior to the industrial period (pre AD 1800), changes in the North Atlantic Ocean, brought about by variations in the Sun’s activity and volcanic eruptions, were driving our climate and led to changes in the atmosphere, which subsequently impacted our weather.

However, this has switched during the industrial period (1800-2000) and changes in the North Atlantic are now synchronous with or lag behind changes in the atmosphere, which the researchers believe could be due to the influences of greenhouse gases.

David Reynolds (Cardiff University), lead author of the study commented: “The results are extremely important in terms of discerning how changes in the North Atlantic Ocean may impact the climate and the weather across the Northern Hemisphere in the future”.

The findings have been published today (6/12/16) in the journal Nature Communications.

The quahog clam, also known as the Icelandic clam, hard clam or chowder clam, is an edible mollusc native to the continental shelf seas of North America and Europe and can live for over 500 years.

The chemistry in the growth rings in the shells of the clam – much like the annual growth rings in trees – can act as a proxy for the chemical make-up of the oceans, enabling researchers to reconstruct the a history of how the oceans have changed over the past 1000 years with unprecedented dating precision.

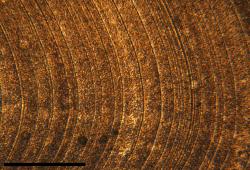

a photograph of the internal growth rings in an ocean quahog shell. The black bar represents 0.3mmBy comparing this record with records of solar variability, volcanic eruptions and atmospheric air temperatures, the researchers were able to construct the bigger picture and investigate how each of these things have been linked to one another over time.

a photograph of the internal growth rings in an ocean quahog shell. The black bar represents 0.3mmBy comparing this record with records of solar variability, volcanic eruptions and atmospheric air temperatures, the researchers were able to construct the bigger picture and investigate how each of these things have been linked to one another over time.

Professor James Scourse, from the School of Ocean Sciences, said: “This is the first time that an annually-resolved record of marine climate for the last 1000 years has been generated from anywhere in the global ocean. This is the most important application of the work of our group in Ocean Sciences since we initiated our research over 25 years ago. The results show how important the output of the sun and volcanic eruptions are in driving the climate, and it’s the first time that the reversal in leads and lags between the atmosphere and the oceans has been demonstrated. This would not have been possible without the annually-resolved records from the shells”.

Up until now, instrumental observations of the oceans have only spanned the last 100 years or so, whilst reconstructions using marine sediment cores come with significant age uncertainties. This has limited the ability of researchers to look further back in time and examine the role the ocean plays in the wider climate system using such detailed statistical analyses.

Co-author of the study Paul Butler, from the School Ocean Sciences, said: “This work demonstrates the problems in basing assessments of marine climate on short instrumental records that cover only a few years at best, and over a time period that has been significantly impacted by human activity. These records will help refine the skill of computer models in predicting future climate change”

Professor Chris Richardson, also from the School of Ocean Sciences, concludes: “These records provide a window into the natural state of the ocean before humanity started having such a dramatic impact on the whole environment, and they also record just how profound that impact has been”

The Bangor-led study was funded by NERC and undertaken in collaboration with researchers from the Cardiff University, University of Exeter, Iowa State University, Aarhus University and the University of Iceland.

Publication date: 6 December 2016