New styles of strikes and protest are emerging in the UK

![]() This article by Emma Sara Hughes, PhD Candidate in Employment Relations, at Bangor Business School and Tony Dundon, Professor of HRM & Employment Relations, University of Manchester was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article by Emma Sara Hughes, PhD Candidate in Employment Relations, at Bangor Business School and Tony Dundon, Professor of HRM & Employment Relations, University of Manchester was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The image of strikers picketing outside factory gates is usually seen as something from the archives. Official statistics show an almost perennial decline in formal strikes. In the month of January 2018 there were 9,000 recorded working days lost due to strikes – a tiny fraction of the 3m recorded in January 1979.

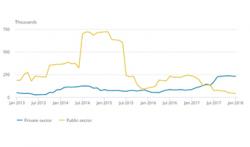

Yet there has been a noticeable increase in private sector working days lost from strike action. In January 2018, the figure stood at 231,000 working days lost. That is 146,000 more days than in January 2017 and 166,000 more than than January 2016.

And it’s not just those on the left who are striking. Workers are also agitated in modern and union-free enterprises. For example, Ryanair was forced to bargain with trade unions after pilots across Europe threatened industrial action, despite its flamboyant CEO, Michael O’Leary, once proclaiming that “hell would freeze over” before his company recognised a union. McDonald’s workers in Cambridge and London also went on strike over pay and zero-hours contracts late last year, with talk of more action to come.

Working days lost in the UK (cumulative 12-month totals, not seasonally adjusted). : Labour Disputes Inquiry, Office for National StatisticsThe beginning of 2018 witnessed some high profile strikes in key sectors: at a number of railways over safety; at water company United Utilities over pay and working conditions; at IT giant Fujitsu over job losses; and thousands of lecturers across more than 60 universities have been striking over pensions.

Working days lost in the UK (cumulative 12-month totals, not seasonally adjusted). : Labour Disputes Inquiry, Office for National StatisticsThe beginning of 2018 witnessed some high profile strikes in key sectors: at a number of railways over safety; at water company United Utilities over pay and working conditions; at IT giant Fujitsu over job losses; and thousands of lecturers across more than 60 universities have been striking over pensions.

What’s all the fuss about?

People are worried about their pay, working conditions, future earnings and security at a time when the world of work is changing.

University lecturers are angered not only at the reduced pension deal being offered by their employers’ group, Universities UK. Views are mixed but many are also aggrieved at their own union, the University and College Union, for recommending an offer that some local activists and members view as falling short on their demands.

Evidently conflict has not been eradicated from modern workplaces. Employees in multiple sectors also protest in other ways such as absenteeism, minor acts of defiance, mischief or sabotage. The Centre of Economic and Business consultancy reports year-on-year increases in absenteeism since 2011. Short disputes and other types of protest are excluded from official strike statistics – hence, many go unnoticed.

Newer patterns of resistance include social media campaigns over precarious zero-hour contracts, “lunchtime protests” such as those at HM Revenue & Customs and Bentley cars, government lobbying by workers at engineering firm GKN over a takeover, or worker sit-ins as staged by hundreds of Hinckley Point power station workers over pay. Meanwhile students have occupied university premises in solidarity with striking lecturers.

The shadow of Brexit

Predicting cause and effect for social phenomena is difficult. Protests are often attributed to employment and economic cycles, combined with changing social values of younger people.

The emergent wave of dissent may indicate we are approaching what some economists call a long-wave “Kondratieff cycle” – named after the Russian economist Nikolai Kondratieff. Here economic cycles can stretch over longer periods – say ten, 20 or 40 years.

If the mid-1990s was an “upswing”, slumping with the 2008 financial crisis, growing dissent may signal another long-wave turning point, fuelled by fears of the UK’s fragile future. For instance, in July 2017 the UK’s fiscal watchdog warned that Britain’s public finances were worse than on the eve of the financial crash. Coupled with the Conservatives losing their majority in government, it may be that the real effect of Brexit is only now materialising and compounding the ill effects of austerity.

Another reason may be because real wages have plummeted, while unemployment is at its lowest since the peak of strike activity in the mid-1970s (now 4.3%), thereby giving workers a greater degree of confidence in pressing their demands.

Changing social values

Another possible explanation is that people now expect more and want immediate change. This is exemplified in shock votes for Donald Trump in the US, Brexit or even Jeremy Corbyn’s popularity.

A new moral consciousness may even have replaced a former industrial working-class ideology. Younger and female labour market participation rates have burgeoned but so too has the gender pay gap and inequality. Multiculturalism, social inclusion, global employment issues are all catalysts for pioneering human rights values for businesses.

People are not satisfied with this status quo and are calling for change. So, as well as the more traditional style of organised action, some workers are expressing this new potential moral consciousness with subtle active protest such as the lunchtime protests, worker sit-ins and social media campaigns.

Analysis also points to “conflict benefits”: for example striking lecturers report lower stress levels, renewed energy and an enjoyment of the solidarity that comes from protest. Research also shows that conflict can support creativity and open disagreement can incite productive outcomes.

Whether we are entering a Kondratieff upswing or witnessing a new active moral consciousness is unclear. Nevertheless, it may be that protest can produce positive outcomes not only for workers, but also help companies to better engage with their workforce.

Publication date: 10 April 2018