In order to conserve biodiversity and safeguard the benefits natural ecosystems provide to humanity, most governments around the world have set themselves a ‘30 by 30’ target to conserve at least 30% of the world’s land and ocean by 2030 (a key goal of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework).

Scientists reviewing 20 years’ worth of data from coral reefs before, during and after a period of unprecedented high sea temperatures in Hawai‘i, suggest that, to ensure the best outcomes for coral reefs, the areas of land and sea targeted for conservation need to be connected.

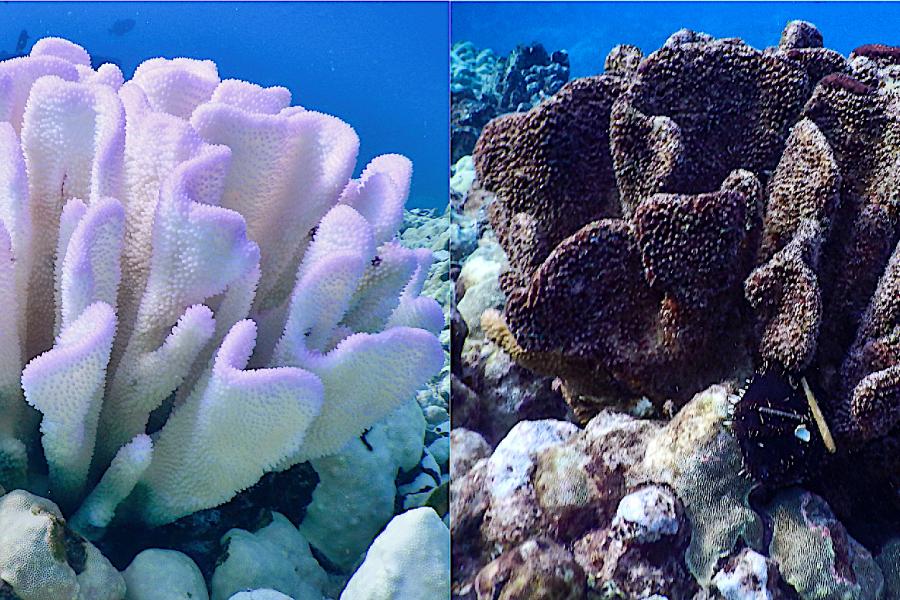

The findings, published in Nature (9/8/23 DOI 10.1038/s41586-023-06394-w), indicate that the coral reef areas which were able to persist before and after the marine heatwave of 2015 had something in common: they had reduced levels of land-based human impacts like wastewater pollution, and more abundant communities of herbivorous fishes that feed on the fleshy algae that compete with reef-building corals for space on the reef floor.

Scientists from Bangor University in the UK and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center conclude that the way to increase the chances of coral reef survival in a warming world is to integrate land-sea coastal management.

“Human impacts at local scales compromise the natural defence abilities of coral reefs, making them more vulnerable to marine heatwaves which are increasing in frequency and intensity under climate change” said Dr Gareth Williams, of Bangor University’s School of Ocean Sciences, a lead author on the paper.

“While governments strive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and slow the pace of ocean warming, management strategies are needed at local scales to mitigate human impacts and support coral reef persistence in our warming world” continued Dr Williams.

“However, thirty percent protection of land-sea coastal areas is impractical and unethical given the high proportion of people that live near and depend on these ecosystems. Instead, we need coupled land-sea policies in any given reef area like wastewater management and fisheries governance for successful conservation outcomes” concluded Dr Williams

Coral reefs need simultaneous land-sea management for survival in a warming ocean

Why are coral reefs important?

Coral reefs support a quarter of all ocean species and are one of the most highly productive and biologically diverse ocean ecosystems on earth. Coral reefs protect the coastline from erosion by waves and are culturally and economically important to their communities. However, many coastal coral reefs are also densely populated areas.

In Hawai‘i, over 85% of the population live within a few miles of the coast, where their infrastructure and activities are concentrated. Inevitably, there are human impacts to coral reefs which occur adjacent to these areas of coastal development, including land-based agricultural runoff of nutrients and sediment that can harm corals and sea-based fisheries that often target the herbivorous fishes that are beneficial to overall reef health. Added to these local human impacts, global climate change is heating the ocean which also threatens reef survival.

Indigenous stewardship practices of island ecosystems considered the land and sea as one connected entity from mountain to ocean. While current coastal management practices have aspired to a similar integrated approach, in practice this has been hindered by the fact that the land and sea are often managed by different local agencies.

"The notion that land and sea are interconnected is deeply rooted in indigenous Hawaiian resource management practices” said Dr Jamison Gove, of NOAA’s Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center and co-lead of the study.

“Traditional Hawaiian resource management stretched from the mountains (mauka) to the sea (makai) and was inclusive of the entire watershed, or Ahupuaʻa. Our findings support the need for reintegrating both land and sea within coastal ocean management, akin to long-standing indigenous stewardship of island ecosystems” continued Dr Gove.

"Looking to the future, climate models predict that ocean warming varies considerably under reduced greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, even within relatively small geographic areas like Hawaiʻi. Actions that support coral reef persistence locally alongside global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions may buy reefs time to adapt and persist into the future,” explained Dr Williams.