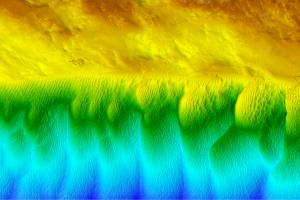

For many species, there is a lack of information needed to make extinction risk assessments - a problem that is particularly acute in biodiverse regions such as Madagascar. Scientists also fear that current methods of assessing extinction risk may underestimate the problem.

A new study has shown that easy to implement genomics methods could accelerate assessment of extinction risk in poorly studied species, but the research paints a gloomy picture of the damage that has already been done.

Madagascar is renowned for its incredible biodiversity, and the island’s plant species are no exception, but the pressures of the modern world are a threat to Madgascagar’s biodiversity. Many Madagascan species are “microendemics” - very rare species that are composed of small, isolated populations that occur nowhere else in the world. How so many of these microendemic species have evolved has remained a mystery.

A team of researchers from Bangor University and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew investigated whether these rare species have always been rare or if human impacts, such as deforestation and extinction of large animals, have made them rare more recently.

The research, Published in Royal Society Proceedings B today (22.9.21) shows that many of the Madagascan microendemics have experienced rapid population declines since the arrival of humans on the island.

A hidden loss of diversity

Alex Papadopulos, senior lecturer at Bangor University explained:

“This highlights that species which have not been assessed or are not considered as threatened may have experienced substantial population crashes in recent history. This hidden loss of diversity means that they may less able to deal with environmental change.

On a more positive note, we have shown that genomics can help to rapidly identify species that need urgent conservation intervention. This could be an invaluable new tool in the conservation toolbox.”

Dr. Bill Baker, senior research leader at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew said:

“At Kew, we’ve studied the palms of Madagascar with our colleagues in-country for over 30 years and have discovered many wonderful species new to science. More than 80% of these are threatened with extinction. For example, Satranala decussilvae , a massive forest fan palm, was discovered as new to science by Kew botanists in 1991, but is already rated as Endangered with perhaps only 200 plants left in North-East Madagascar. This study shows that Satranala was much more abundant in the past and is in steep decline – it tells us that the time to act is now.”