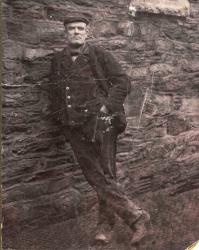

This photograph appeared in

Yr Herald Cymraeg on 22 February 1910.

With thanks to the Daily Post and

Gwynedd Archives Service. Also to

Barry Hillier and Rhodri Clarke for

drawing my attention to it.

On Boxing Day 1909 the residents of Holyhead awoke to shocking news. The previous night a 35 year old woman called Gwen Ellen Jones had been brutally murdered in a field behind Newry Street, one newspaper graphically reported that her head had been nearly severed. Her killer, 49 year old William Murphy, gave himself up and was committed for trial at Beaumaris Assizes.

There were sensational scenes at Murphy’s court appearances; a man fainted, men climbed in through the windows and there was ‘great disorder and commotion’ when women were ordered out due to the disgusting details which would be heard. On his entry into court Murphy was greeted with hissing which he acknowledged with a grin, as if a villain in a Victorian melodrama. Outside Beaumaris Courthouse a large hostile crowd waited for him and several small children were injured as it surged forward towards Murphy ‘the police men having as much as they could do to keep the mob from attacking him’. On Wednesday 26 January 1910 Murphy was found guilty after the jury deliberated for only three minutes, and he was sentenced to death.

The story appeared in newspapers up and down the country. Some argued for Murphy’s life and David Lloyd George’s brother started a petition on grounds of insanity. However, the sentence stood and Murphy was hanged at Caernarfon Gaol on Tuesday 15 February 1910.

William Murphy’s name has remained a familiar one as he was the last man to be hanged at Caernarfon Gaol. Even a ballad was written called ‘Execution of Murphy’, but what about the woman he killed? What is known about Gwen and the circumstances that led to her murder, and what happened that Christmas night in 1909? It is now 110 years since her death and it is therefore time that local woman, Gwen Ellen Jones, is remembered as a person in her own right and not just as a footnote to William Murphy’s story.

Slate Miner’s Daughter

Gwen was born in Blaenau Ffestiniog in 1874, the daughter of slate miner John Parry (originally from Llanddonna) and his wife Jane. The couple’s first child (a daughter called Gwen) died aged 10 and when Gwen Ellen was born a few months later she was named after her deceased older sister. Two younger siblings followed, Thomas John in 1879 and Jane in 1886.

In the 1890s Gwen’s mother died and the family moved to Llanfairfechan where Gwen’s father found work as a labourer in the stone quarry nearby. In 1898, 23 year old Gwen married 43 year old local man, Morris Jones, also a labourer in the stone quarry. By 1901 they were living at 4 Tan y Bonc at the top of Llanfairfechan and her father, who was not in the best of health, and younger sister moved in with them. Gwen had also adopted a two year old girl called Gwladys Jones who, reports said, was born in Llanrwst workhouse and abandoned by her mother. Taking Gwladys in was a further drain on the family’s limited resources, but Gwen did so nonetheless, and all her life Gwladys looked on Gwen as her mother. Clearly Gwen was at the centre of a family who depended on her.

Gwen also took in two lodgers to make ends meet which meant that living conditions at 4 Tan y Bonc would have been cramped and unpleasant. The house had just three rooms, a kitchen and two bedrooms, and these now had to accommodate seven people. Alongside all of this Gwen took in washing and, fatefully, this was the first step on the road to her death in Holyhead.

Corporal William Murphy

With thanks to Gwynedd Archives Service.

In 1902 William Murphy started bringing his washing to her. He was a powerfully built man who had spent many years in the military, first with the East Lancashire Regiment where he served in India and South Africa, and then as a 2nd Corporal in the Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers (militia). He was a man who people both liked and feared. He had a sense of humour and fun and even allowed himself ‘to be tied with ropes on the occasion of the May Day sports at Llanfairfechan’. At the same time his powerful stature meant that no man wanted to cross him. Whilst in the Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers he was described as ‘a most fearless man’ and singlehandedly overpowered a violent drunk brandishing a bayonet who was ‘quite helpless in his grasp.’ The fact that he carried a piece of soap and a mirror suggests that he took care of his appearance, and he might have come across as a bit of a swashbuckler to Gwen with his military background and overseas service.

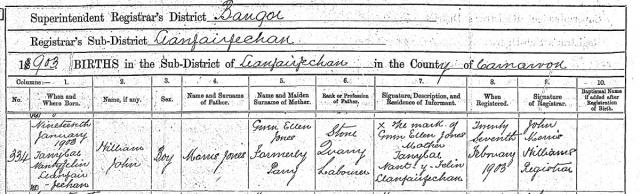

It is impossible to know whether Gwen and Morris Jones’ relationship was a happy one, but in four years of marriage no child appears to have been born to them. Whatever the truth of the situation, Murphy and Gwen embarked upon an affair and the birth of Gwen’s son on 19 January 1903 was most likely Murphy’s child; she named him William John after her lover and her father. How Morris Jones reacted, we do not know, but the length of time taken to register the birth might be evidence of his knowledge of the child’s true parentage, and reluctance to put his name on the birth certificate (which he eventually did).

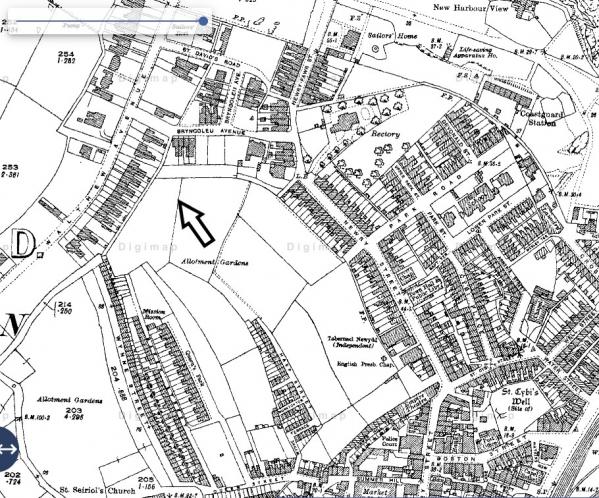

© Crown Copyright: Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Murphy, who was a jealous and possessive man, no doubt urged her to leave her husband. Naturally the situation could not continue and Gwen did leave her husband on more than one occasion to be with Murphy. Clearly it would have been difficult for her father to remain in the marital home while all this was going on so he moved to 21 Cae Star, Bethesda (the site of the pay and display car park near Neuadd Ogwen).

A ‘Common Lodging House’, Holyhead

Gwen’s actions would have been considered so shocking that friends and neighbours would now be former friends and neighbours and she would have been cut off from all those she had known before. Finding work locally would be difficult due to the scandal, yet she had two children to support. In addition, her brother had moved to South Wales, meaning she had no male protector except her father who was no match for Murphy. This left her in a perilous situation as she was now reliant on Murphy for financial support and things began to go from bad to worse.

To avoid taking the scandal to her father’s new home at Cae Star in Bethesda, Gwen rented a room on the top floor in what was termed a ‘common lodging house’ at 51 Baker Street, Holyhead, a very poor area of the town. She stayed here with Murphy, but when he was away working she returned to her father’s home in Bethesda. Since 1908 Murphy had been in the Royal Anglesey Royal Engineers (Special Reserve) which gave him occasional employment. The rest of the time he obtained labouring jobs where he could such as on the Pentraeth new Railway Line, with the Holyhead Waterworks Company and even travelled as far as Cornwall and Yorkshire. A lot of the time the couple lived from hand to mouth and were often reduced to begging. As if this wasn’t bad enough, Murphy had become violent towards her. Her father testified that Murphy had beaten her ‘black and blue’ while both Gwen and Morris told him that Murphy had once cut her shoes off with a knife, had also threatened her with a knife and kicked her several times.

It is a testament to Gwen’s courage that she attempted to leave Murphy, and she took the opportunity to do this while he was away working in Yorkshire in 1909. Whilst Murphy claimed he sent her money Gwen still needed to earn her own income to make her independent of Murphy. We cannot know for certain, but it may be that this led her into prostitution. The North Wales Express blatantly referred to her as a prostitute, whilst other newspapers referred to her variously as a ‘beggar’, Murphy’s ‘paramour’ or a member of the ‘hawker class’. Certainly, two female residents of Baker Street had been convicted of soliciting in 1903. Her friend of about a year, Lizzie Jones (Elizabeth Glynn Jones) from Llansadwrn, also had lodgings at 51 Baker Street and might have been the person who introduced her to it. This is suggested by Murphy’s reaction when he saw them together. During one of his court appearances, while Lizzie was giving evidence, he shouted across the courtroom

‘That’s the woman that caused her death. When I see’d her with Gwen Ellen Jones I know’d it was all up with her. I know’d she was a bad ‘un before, but when I saw her with this ‘un I know’d she was worse’.

Certainly, Murphy and Lizzie had a vicious slanging match across the court room during which Murphy levelled various accusations against her and she screamed ‘You are a liar, and hanging is too good for you.’

Ending It With William Murphy

About six weeks before Christmas, while Murphy was away, Gwen left Bethesda for Holyhead where she took up with another man, Robert Jones, and according to Jones they lived together as man and wife. However, their relationship seemed to be one of convenience with Jones showing little affection for her. A week or two before Christmas Murphy arrived at John Parry’s house in Bethesda looking for Gwen. He might have suspected that she had taken up with someone else because he told Gwen’s father and adopted daughter, Gwladys, that if he saw her ‘with any other man he would kill her’.

Gwen’s father lied and told Murphy she had gone to Beaumaris with her husband, specifically to deter Murphy from following her, but it was inevitable that he would go to Holyhead and he arrived there two weeks before Christmas. He took lodgings nearby at 40 Baker Street and was barely able to supress his jealousy:

‘I came here, and found her living with that man Bob Jones. That riled me and I was in a common lodging-house and him sleeping in company with my woman. I could not stand that.’

A bizarre scene then ensued when Murphy was invited to join them for breakfast one morning with the nonchalant Jones appearing to think nothing of it. Despite her co-habitation with Jones, Gwen once again found herself begging around the area with Murphy who was again violent towards her. On Wednesday 22 December ‘he appeared to have given her a thrashing’ and told a John Griffiths ‘I will do for her if I can’t get her away from that old man’. Griffiths also saw Murphy strike her ‘on the nose with his fist’. Gwen told Lizzie and Robert Jones that on more than one occasion Murphy had shown her a knife and a rope and warned ‘she would get one or the other’ if she did not go to South Wales with him. Evidence suggests that at no point did Jones try to defend her or warn Murphy off.

Gwen’s Murder

On the fateful night of 25 December 1909, Murphy arranged to meet Gwen at the bottom end of Wynne Street, near a stile, but Gwen went to a pub near the station for a drink with Lizzie instead They then went to the Bardsey Island Inn where they met Murphy outside. He asked Gwen if she would go for a walk with him, and she agreed. Lizzie started to follow but Murphy told her that he wanted to see Gwen alone. It was 8.30pm as they walked up Newry Street in the direction of Captain Edward B Tanner’s house and it was stated that they were singing. This was the last time Lizzie or anyone else saw Gwen alive.

Limited (2019). All rights reserved. (1920). With thanks to Holyhead Historian, Barry Hillier, for this information.

It was Christmas night and Gwen had been drinking, so her judgement and reactions were impaired, making her even more vulnerable. As they walked in the darkness there was a steady drizzle of rain which soaked their clothes. Gwen, walking first up the street and then over a field was stumbling against him and, in her drunkenness told him that she liked him, no doubt remembering their early courtship. She was dressed in similar clothes to those in the photograph, wearing a hat and a little boa around her neck. As a pretext, Murphy asked her why she didn’t take her boa off and she explained that it was hooked underneath. He moved his hands to her neck but instead of releasing the boa, he gripped her throat with his left hand and pushed her to the ground. Gwen, however, desperately fought back; she screamed and struggled and Murphy stated that ‘we had a good hard fight . . .she was nearly as strong as me’ and she scratched his face badly. But inevitably she was no match for him as he knelt over her, crushing her neck with his left hand and steadying himself with his right only ceasing after ‘she grew weaker and weaker’ and ‘gave her last kick’.

After this, Murphy’s brutal treatment of her body increased the horror of what he had done, and we can only hope, though it is not certain, that she died from his first assault. He took out a knife and started cutting her throat, putting her head across his leg to do so. As she was gurgling Murphy believed she was still alive as he then dragged and pushed her body into a nearby ditch where he continued to cut her throat clean across five inches, severing everything but the spinal cord, before pulling the wound apart with his hands to a width of three inches.

He then ‘turned her face downwards, and shoved her underneath the water to smother and drown her.’ Once this final attack was over, he attempted to drag her body out of the ditch by her hand but she was too heavy, her clothes being soaked from the rain and water from the ditch, so he tried to drag her out by her hair. Again he failed and so he let her blood soaked, mutilated body roll back into the ditch. When the police found the body they described it as lying on its back, the clothing around the neck and shoulders covered in blood with ‘a ghastly wound in the neck and one hand covering the throat, as if she had tried to protect it.’

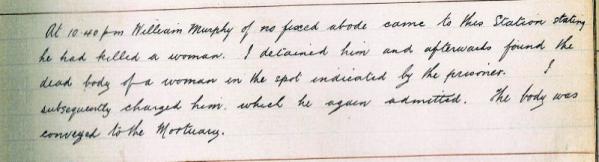

Following the murder, Murphy at first planned to flee the area and sold his overcoat and some food to raise the money to do so. However, after returning to Gwen’s lodgings he decided to give himself up. Lizzie and neighbour John Jones (known as Johnny Flammiau), were there and asked him where Gwen was to which he replied ‘You have seen Gwen for the last time.’ Murphy and Gwen’s son, seven year old William, was also there and crying for his mother, but Murphy told him he had no mother and gave him a penny, before telling Johnny Flammiau to give him some bread. He then showed Johnny Flammiau the body and proceeded to the Police station where he gave himself up.

by Superintendent Prothero Courtesy of Anglesey Archives.

It appears that the Holyhead Police discovered letters on Gwen’s body which provided her father’s address, and a telegram was sent to the Bethesda Police Station. The harrowing news was broken to Gwen’s 62 year old father, probably by Sergeant Rowlands of Bethesda, and he travelled to Holyhead to identify the body. His circumstances were such that the inquest jury made a collection to pay for his travel, food and lodgings in Holyhead.

The horrific events of that night were reported in newspapers across the country and at the trial even Gwladys Jones, Gwen’s 11 year old step daughter, was forced to give evidence, at one point breaking down in tears. It must have been a traumatic experience for Gwladys and Gwen’s father, John. Just in front and below the witness box the gentleman of the press were crammed together on a bench writing down everything about Gwen’s life and horrific murder. A mere few yards across the court room Murphy faced them from the dock, often firing questions at the various witnesses.

the dock to the witness box, from where Gwen’s father and adopted daughter gave evidence. The witness

box is to the left under the light, the reporters bench to it’s immediate right. The dock where Murphy stood

is on the extreme right of the photograph.

Murphy’s defence argued that he ‘never really had any intention of doing harm to the woman, but was possessed by some impulsive mania, and unable to control his actions’. However, Murphy’s actions and statements prior to that night suggest that the murder was premeditated. On the train to Caernarfon Gaol, about a mile and a half out of Holyhead, he pointed to a farm and told his police escort that he had initially intended to kill Gwen there on the Thursday (23rd) while they were out begging together, but as William was with them he decided against it because he did not want the child to see it. He carried a knife and cord around with him and in conversation with men from Baker Street was alleged to have said ‘that he would do for Gwen Jones, and that she would not live to eat her Christmas dinner’. After the murder Murphy was reported as saying ‘I am not sorry for it; I am glad I have done it. I shall get a bit of rest now.’ According to the policemen at Holyhead who came into contact with him at the time of the murder, he gloried not in the fact that he had murdered her, but that ‘he had prevented her from bestowing her affection on any other man but himself.’

Gwen’s Burial

Whilst the furor around the murder and forthcoming trial raged on in the newspapers, Gwen was quietly laid to rest in an unmarked pauper’s grave in the Mortuary Cemetery (Maeshyfryd), Holyhead on 29 December We do not know who, if anyone, attended her funeral which was conducted by the retired Rev David Powell Richards, who just happened to be visiting the area over the Christmas holidays. (Thanks to Barry Hillier for information about Rev David Powell Richards).

Gwen’s Children

Gwen’s children were now left in a precarious situation. Gwen’s father disappears from history after the trial and he might have died. Her brother, Thomas, appears to have made no attempt to take the children into his home in South Wales. Perhaps he couldn’t afford to, he already had a wife and three children to support, or perhaps he wanted to avoid association with these events and so kept his distance. The press appear not to have made any mention of him, yet police letters reveal that he knew of his sister’s murder.

Gwladys was taken into care by the Bangor and Beaumaris Union and placed in Maesgarnedd Home, while William John was taken into the care of Dr Barnardos. He was taken away from the home in April 1910 by a man who used him for begging purposes, but fortunately someone found them on one of the Caernarfon Roads and William was taken back into care. It is significant that Morris Jones, who remained a silent figure in all of this, not appearing at the trial or giving any statements, did not come forward to take care of William, something that would have been expected if the child had been his. In April a lady from Bolton offered to adopt Gwladys and the local board of guardians accepted without getting the agreement of her mother who had returned from South Wales and was now in Ffestiniog. They did so because they did not want to lose this opportunity for Gwladys and they were ‘prepared to go to gaol over it’. We do not know whether William and Gwladys ever saw each other again, but with Gwen’s death in 1909 the precarious little family unit that had survived until then, fell apart.

Gwen Ellen Jones

In this, the 110th year since her death, Gwen Ellen Jones should be remembered, not as part of William Murphy’s story, but as someone in her own right. She was her own person and she made mistakes, but she also showed resilience and kindness. She was John and Jane’s daughter, Thomas and Jane’s sister, Morris’ wife and William and Gwladys’ mother and that is how she should be remembered and not merely as a woman of ‘the hawker class’ who was murdered by William Murphy on Christmas night 1909

Gwen Ellen Jones 1874-1909

Gwen’s Possessions 25 December 1909

|

Murphy’s Possessions 25 December 1909

|

Dr Hazel Pierce

The Stephen Colclough Centre for the History and Culture of the Book.

December 2019

SOURCES

Birth Certificate of William John Jones, 19 January 1903

Anglesey Archives

WH/8 Cases Tried Anglesey Constabulary Second Division 1904 - 1919

WH/17 Records of Crimes Book 1896 - 1922

WH/39 Journal Holyhead Station 1909 - 1912

WH/53 Letter Book 1893 - 1911

On-line Sources

The Census Returns for Wales: 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911 (via Ancestry.co.uk)

General Register Office England and Wales Birth, Marriage and Death (BMD) Index (via Find My Past and the General Register Office)

Parish Registers for Caernarfonshire and Anglesey (via Find My Past)

Newspapers

(on-line via The National Library of Wales and Find My Past)

Lancashire Evening Post, 28 December 1909

Flintshire Observer Mining Journal and General Advertiser for the Counties of Flint, 30 December 1909

The Cambrian, 31 December 1909

Llangollen Advertiser, 31 December 1909

The North Wales Weekly News, 31 December 1909

Evening Express, 4 January 1910

Caernarfon and Denbigh Herald, 7 January 1910

The North Wales Express, 7 January 1910

The North Wales Weekly News, 7 January 1910

Llandudno Advertiser, 8 January 1910

Evening Express, 27 January 1910

Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 28 January 1910

The North Wales Express, 28 January 1910

Weekly Mail, 29 January 1910

The Montgomeryshire Express and Radnor Times, 1 February 1910

Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 4 February 1910

Baner ac Amserau, February 9, 1910

Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 11 February 1910

Rhyl Record and Advertiser, 12 February 1910

Llandudno Advertiser, 12 February 1910

Evening Express, 14 February 1910

The North Wales Express, 18 February 1910

Carnarvon and Denbigh Herald, 29 April 1910