ISWE in conversation with … Dr David Gwyn on the Slate Landscapes of Gwynedd

To celebrate the launch of our new website, we are inviting several of our partners and friends to discuss their work, passions and interests. Today we are in conversation with Dr David Gwyn on the Slate Landscapes of Gwynedd.

David is a prominent archaeologist, historian and heritage consultant, with a lifelong passion for and expertise in the industrial heritage of north Wales. In particular, he is a leading specialist in the archaeology of Gwynedd’s slate industry, an industry synonymous with the region’s economic, social, political and cultural history.

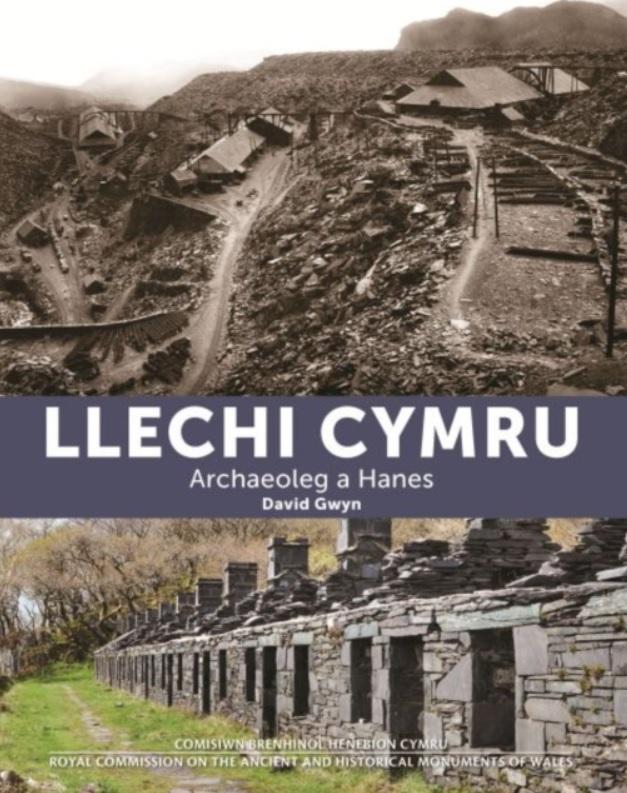

David played a central part in the long-term effort to have the ‘Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales’ designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the award of this status in 2021 was in large part thanks to David’s drive, vision and intellectual contribution. His book, Llechi Cymru: Archaeoleg a Hanes, published in English as Welsh Slate: Archaeology and History of an Industry (2015), is the foundational text on this ‘most Welsh of Welsh industries’, and the significant impact it had on many facets of local Welsh life.

In this fascinating conversation, David discusses the importance of slate to the modern history of north Wales, the significance of the area’s estates in shaping and cultivating this industry, and its corresponding landscape, and recounts the successful process to secure Gwynedd’s UNESCO World Heritage recognition.

David, could you tell us about your background and how you first became interested in the landscape and industry of slate?

I am Bethesda-bred, and my family had connections with Rhiwbach and Cwm Machno quarries. Visits to Penrhyn Quarry from 1962 to 1964 first made me realise how interesting these places were.

How and when did you become involved in the formal process to secure UNESCO World Heritage Status for the slate landscapes of Gwynedd?

I initiated the process following the successful inscription of the Pontcysyllte aqueduct and canal in 2009, with which I was involved, by recommending it to the then cabinet lead in Gwynedd Council.

What was your role in developing the case for the nomination?

I made the initial suggestion; subsequently developed the case; prepared the application to go on the UK tentative list; worked with academic colleagues to prepare comparative studies; published the definitive study of Wales Slate with RCAHMW; established the consultancy team; evaluated the sites for inclusion – the extractive sites above and below ground, transport routes and communities; had primary responsibility for sections 1-3 of the Dossier submitted to UNESCO; cooperated with Gwynedd Council, Cadw, RCAHMW and other project partners throughout; liaised with the Department of Culture, Media and Sport; and participated in the assessor’s visit.

Why are the slate landscapes of Gwynedd considered to be of global significance to humanity?

As outlined in the Dossier, they are an outstanding example of a stone quarrying and mining landscape which illustrates the extent of transformation of an agricultural environment during the Industrial Revolution. Massive deposits of high-quality slate defined the principal geological resource of the challenging mountainous terrain of the Snowdon massif. Their dispersed locations represent concentrated nodes of exploitation and settlement, of sustainable power generated by prolific volumes of water that was harnessed in ingenious ways, and brought into being several innovative and technically advanced railways that made their way to new coastal ports built to serve this transcontinental export trade. The property comprises the most exceptional distinct landscapes that, together, illustrate the diverse heritage of a much wider landscape that was created during the era of British industrialisation.

The landscape also exhibits an important interchange, particularly in the period from 1780 to 1940, on developments in architecture and technology. Slate has been quarried in the mountains of Northwest Wales since Roman times, but sustained large-scale production from the late 18th to the early 20th centuries dominated the global market as a roofing element. This led to major transcontinental developments in building and architecture. Technology, skilled workers and knowledge transfer from this cultural landscape was fundamental to the development of the slate industry of continental Europe and the United States. Moreover, its narrow-gauge railways – which remain in operation under steam today – served as the model for successive systems which contributed substantially to the social and economic development of regions in many other parts of the world.

Slate was and is evidently of huge importance to the region’s economic, social, political and indeed cultural identity?

Yes, the Slate Landscape is an outstanding example of the industrial transformation of a traditional human settlement and marginal agrarian land-use pattern; it also exemplifies how a remarkably homogeneous minority culture adapted to modernity in the industrial era yet retained many of its traditional attributes.

The monumentality of the quarry landscapes is compelling; huge stepped working benches carved from the mountainsides, deep pits and vast tips, and extensive cavernous underground workings. These also indicate the relentless persistence of generations of workers who used their hard-won skill and innovative technology to exploit slate for a global market.

Their settlements, created by the industrialists, the workers and their families, retained multiple aspects of the traditional way of life and its strong minority language. They remain a palpable ‘living’ testimony, just like the diminished but proud slate-working tradition, and the railways that once hauled the slate.

Was it challenging to balance this global story with the intensely local/regional importance of slate?

Not a challenge; the story is global but is manifest at a very local level.

Can you explain why landed estates such as Penrhyn, Faenol and Tan-y-Bwlch are central to the history of slate quarrying, and what their roles were in shaping and changing Gwynedd’s landscape?

Landed estates are central to early British industrialisation. Owners of estates had the capital and banking links that were necessary to open out quarries and mines, build railways and mills and thereby to transform a small-scale craft-industry into a major global supplier. Estates went about the process in different ways – Penrhyn, Vaenol, Oakeley, Glynllifon, Kinmel and the crown all followed different approaches. Fluid capital was also more important from the 1850s onwards.

Is there a particular landscape feature which exemplifies the slate landscape designation?

The Slate Museum is central to interpretation of the site.

Which areas of research need to be developed in order to more fully understand the history of slate?

Finance, banking and sales.

What are your hopes for the long-term impacts of the designation for the communities of Gwynedd?

Increased community pride; community awareness of heritage; economic amelioration; sustainable tourism and improved participation in tourism by Gwynedd residents; and informed conservation.

To find out more about the Slate Landscape World Heritage Site, please visit https://www.llechi.cymru/.