New research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, shows that plasticity that has evolved to deal with one stressful situation, can help plants to adapt rapidly to new stressful situations and conquer new habitats.

Sea campion, a coastal wildflower from the UK and Ireland, is regularly exposed to salt spray, which is harmful to many plants. In the last few hundred years, it has colonised and adapted to toxic, zinc rich industrial-era mining waste, where very few plants can survive.

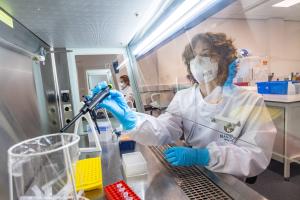

To understand how salt-plasticity aids in adapting to zinc contamination, a team of researchers led by Bangor University conducted experiments on sea campion.

By exposing the mine and coastal plants to both salt and zinc and measuring changes in the expression of genes in the plant’s roots, the researchers were able to see how plasticity in the coastal ancestors acted as a preadaptation, which helped the plants transition more easily to surviving on mines.

Alex Papadopulos, Reader at Bangor University explained, “To cope with salt exposure on cliffs and shingle beaches, Sea campion has evolved plasticity to cope with this variable stress. Remarkably, when industrial mining opened a new niche that other plants were not able to use, sea campion has exploited its salt responses to adapt to a completely different type of stress, explaining why the mine plants adapted so quickly.”

Sarah Coates, PhD student at Bangor University added, “Our experiments revealed the importance of ancestral habitat stress-responses during adaptation to new habitats, which, to our knowledge, has not been observed before in this way.”

Alex continued, “We were really surprised by how much of an influence this ancestral salt-plasticity has had on adaptation to the mines. It’s also astonishing that it happens in multiple different ways. It all suggests that organisms with high levels of plasticity may also be much better equipped to deal with rapid environmental change.”