Using Rhyl in North Wales as a case study, this project modelled the benefits of existing and planned green infrastructure (GI). It assessed the community’s perceptions of these environmental changes happening in their neighbourhood.

See also:

Selling Sustainability: using enterprise thinking to promote the benefits of sustainability to our community.

We aimed to ‘translate’ our research and expertise into easy-accessible and digestible information to inform and inspire the audience as regards taking climate action. The project delivered a workshop to capture views from the Bangor University student community about barriers and facilitators to engaging for the climate and how enterprising thinking can be a tool to promote environmental sustainability to the wider community. We shared these insights via short videos and a podcast, and the insights fed into future curriculum development.

This project was funded by the Bangor University Enterprise Development Fund (2023–2024) and supported by the Bangor University Undergraduate Internship Scheme (2023–2024).

Written by Jenna Burns

There are many factors that influence how we interpret and prioritise efforts against climate change and this in turn influences how humans interpret the severity of the issue. The 3 most prevalent factors that are involved in climate change negation are the media, word choice and politics.

So, what role does the media play? Firstly, lets address how climate change information is reported. When the climate change conversation is addressed by the mass media, it is often presented as a balanced debate. This has an influence on how people perceive climate change, as if it is presented as 50% credible and 50% deniable, people may feel that the significance of climate change is disputable and so will disregard the need for change.(1)

When people become disinterested in the climate change crisis, the media also addresses climate change less. For example, during the time of Donald Trump’s presidency, when he removed himself from the Paris agreement, there was less media coverage of climate change in the US, which in turn, reduced the urgency for climate change action.(2)

According to Sniderman, when people are confronted with a concept such as climate change, they are “unlikely to spend time acquiring copious amounts of information and are very selective about what they pay attention to” and as a result will take shortcuts and look towards the media for small snippets of information rather than academic sources.(3) This becomes an issue when the media reduces the amount of screen time given to climate change, such as during the Trump presidency, as less people are able to access the discourse and as a result are less likely to internalise the issues and make changes towards a more conscious future.

Alongside the lack of coverage, the media has also contributed to the uncertainty of the topic through word choice. Using words such as ‘might’ or ‘may’ in news reports when referring to weather forecasts or climate change predictions can make people believe that there is a substantial chance that the climate predictions on sea levels and temperatures rising could in fact not happen thus allowing for the urgency of the issue to dissipate.(4)

It is not just the media however that is using this complicated language. It can be said that scientists often use words that to laymen, are confusing. An example of this would be the use of the term ‘positive trend’ which is often used in the media and in scientific reports. To laymen this can seem like a good thing and so they may be more likely to deny the need for climate urgency, however what scientists should really be saying is ‘upwards trend’ to accurately depict the situation and to reduce confusion.(5) The role of language therefore plays a large role in the climate change discourse and when educating people on the topic of global warming.

Besides confusing language, alarmist language, which involves exaggerating a situation through words that lead to panic and fear, is often used by politicians. This could explain the huge disparity in numbers of climate change believers and non-believers within government, as they are conflicted on what to believe. Another factor could be the implications that climate change policies would bring to individual parties. According to McCright and Dunlap, conservatives see environmental regulations as threatening to core elements of conservatism. For example, a binding treaty on carbon prices is seen as a direct threat to sustained economic growth and so conservatives and other right-wing parties will be more likely to deny climate change in an attempt to self-preserve and to evade having to implement more eco-friendly policies that could dampen their growth. They will therefore avoid the topic when addressing the public thus obscuring their supporters’ views on the topic.(6) This sustained division is mirrored in American Republicans also. Where 75% of democrats believed that global warming was the result of human action in the US in 2009, only 19% of republicans believed as such6 and with Donald Trump electing Scott Pruitt, a climate change denialist and close ally of the fossil fuel industry to lead the Environmental protection agency in 2016, one can see the sustained position that right wing parties hold on climate change.(7)

Suggestions to improve the climate change discourse:

- Accurate reporting

- Using playful and imaginative language rather than alarmist language when addressing the public = positive results and acceptance of climate change8

- Using metaphors to differentiate between often confused concepts e.g. Climate vs. Weather (8)

- Inoculating the public against climate change misinformation

- Highlighting the scientific consensus – NASA + ipcc websites

References

- Reiner Grundmann, and Ramesh Krishnamurthy. ‘The discourse of climate change: A corpus-based approach.’ Critical approaches to discourse analysis across disciplines (2010): 4.2, 125-146. (P. 1) <https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/10425/1/Grundman_and_Krishnamurthy.pdf> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- David J. Park, ‘United States news media and climate change in the era of US President Trump.’ Integrated environmental assessment and management (2018): 14.2, 202-204. <https://setac.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ieam.2011> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- Susan. McDonald, ‘Changing climate, changing minds; applying the literature on media effects, public opinion, and the issue-attention cycle to increase public understanding of climate change.’ Int J Sustain Commun, 4 (2009): 45-63. (p.3)

- <http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.334.1015&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- James. Painter, ‘Climate change in the media: Reporting risk and uncertainty.’ (2013). 1-176 (p.57) <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/bangor/reader.action?docID=1414044> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- Brigitte Nerlich, Nelya Koteyko, and Brian Brown. "Theory and language of climate change communication." Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1.1 (2010): 97-110. <https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.bangor.ac.uk/doi/full/10.1002/wcc.2> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- Haydn Washington. ‘Climate change denial: Heads in the sand.’ Routledge (2013) 1-159. (Pp.89-90) <https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=snk1CLf9ZbYC&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=climate+change+and+denial&ots=YgoZiboHov&sig=aFKj6SRE9_BFjBv2HlwYSkUl_Wo&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=McCright&f=false> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- Coral Davenport, and Eric Lipton. ‘Trump picks Scott Pruitt, climate change denialist, to lead EPA.’ The New York Times, 7 (2016). <http://scholar.googleusercontent.com/scholar?q=cache:wyincr1SHc8J:scholar.google.com/+Donald+trump+picks+scott+Pruitt,+climate+change+denialist+and+close+ally+of+the+fossil+fuel+industry+to+lead+Environmental+protection+agency+&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5> [Accessed 26 April 2021]

- Brigitte Nerlich, Nelya Koteyko, Brian Brown. “Theory and language of climate change communication”

The Slate Landscape project explores locals' and tourists' emotional reactions/levels of place attachment to the area, following its recent successful bid to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It addresses the concerns around sustainable tourism that people may have moving forward, particularly as North Wales is already a popular staycation destination. Changes in perceptions of place branding and heritage tourism are also interesting to explore.

Useful Links

- Llechi Cymru

- Potential damage to the environment/landscape

- The need for sustainable tourism

- Social determinants of place attachment at a World Heritage Site

- World Heritage Sites and climate change

What role do forests play for natural flood management in the UK?

Recently published research conducted by Bangor University and Forest Research reviews the current state of knowledge on the role of forested lands for natural flood management (NFM) in the UK. Published in the WIREs Water journal (https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1541), the review examines the existing evidence on the role that different types of forest cover play for NFM.

The authors specifically looked at four different woodland types: catchment, cross-slope, floodplain, and riparian, to determine the relative merits of each type and their effectiveness in mitigating flood risk. They found that while there is good understanding of the processes involved and some evidence that carefully planned and managed woodland can mitigate flood risk, the published data for this evidence base is somewhat sparse. This may be either due to the long timescales needed to conduct comprehensive studies or the relative infancy of the research on NFM.

Matt Cooper, the lead author and KESS 2 East PhD candidate at Bangor University, explains: ‘I think that this is a very interesting study to answer what seems to be a very simple question, “if a valley has trees up the sides, will the stream at the bottom have a lesser flow following heavy rainfall than if there are no trees?”. The intuitive answer is of course “yes”, but at the moment there is very little quantitative evidence for this for large floods, as our review shows. Natural flood management is gaining a lot of traction and increasing the forest cover in our catchments is one of the strategies for mitigating flood risk. Our review indicates that more work is needed to better quantify the effect that different woodland types and placements can have on catchment flood peaks.’

Image:The different forest types looked at in the review paper.

Dr Sopan Patil, Lecturer in Catchment Modelling and co-author of the paper, adds: ‘Flooding is a complex issue and affects us all in the UK. Although it has been suggested that NFM techniques, such as floodplain restoration, leaky barriers, woodland creation, and runoff management, can be used as cost-effective supplements to our existing flood defence infrastructure, their effectiveness for mitigating flood risk is not fully understood. Our review highlights the need for more research on using woodlands as a NFM strategy. This is especially important for the UK, as policy makers are increasingly looking towards nature-based solutions to mitigate the potential impacts of climate change.’

Dr Tom Nisbet, Head of Physical Environment Science in Forest Research, commented ‘Climate change is expected to lead to an increased frequency of flooding, with some evidence that this is already happening. Trees and woodlands have an important role to play in helping society adapt to a warmer world, including in managing flood risk. This review highlights the need for further advances in understanding and modelling to better guide future planting and woodland management for flood alleviation.’

Matt is funded by Forest Research and KESS 2 East:

Knowledge Economy Skills Scholarships (KESS 2 East) is a pan-Wales higher level skills initiative led by Bangor University on behalf of the HE sector in Wales. It is part funded by the Welsh Government’s European Social Fund (ESF) convergence programme for East Wales.

Forest Research is Great Britain’s principal organisation for forestry and tree-related research and is internationally renowned for the provision of evidence and scientific services in support of sustainable forestry. A fact sheet ‘Climate change, flooding and forestry’ is available here: New Factsheet: Climate change, flooding and forests - Forest Research'

@Forest_Research

Current research projects include:

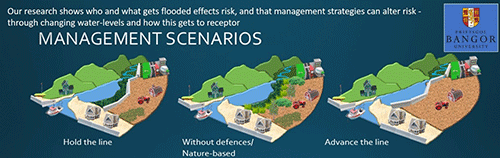

The NERC funded “SEARCH” project: https://www.ukclimateresilience.org/projects/search-sensitivity-of-estuaries-to-climate-hazards/. PI Peter Robins said: “Recent near-miss flooding in the UK (Dec-2013, Jan-2017) could have been much worse with subtle changes in sea level-precipitation behaviour and timings, although still caused damage costing £500M. Twenty million people living near UK estuaries are especially vulnerable to flooding as sea levels rise combined with extreme storms, precipitation, heatwaves and droughts that are becoming more intense and seasonal. SEARCH will use past and new observations with UKCP18 projections of precipitation, temperature, fluvial flows, storm surge and sea level applied to coupled hydrodynamic-groundwater models to simulate flooding hazards. It will evaluate how climate projections downscale to flooding impact, providing crucial inundation and likelihood data for the EA, NRW and SEPA to identify the most vulnerable communities to flooding and to manage their resources during incidence response.”

Mirko Barada is a PhD student funded through the Cemlyn Jones Trust, using historical data to explore future flood risk at the School of Ocean Sciences. Previous flood risk research has predominately focused on changes to the sources of flood hazard, such as sea-level rise or predictions of heavier rain in the future. Here, we are using numerical models to simulate the effect of receptors in the flood risk framework; by using historical data we can develop scenarios of how people and flood water interact with the flood defences to change risk.

Thomas Clough is a PhD student funded by Welsh Water through the ERDF KESS scheme, to explore future flood risk at the School of Ocean Sciences. Previous flood risk research has predominately focused on impact of a flood scenario using inundation extent or the height flood waters reach. Here, we are using state of the art ocean flow models to simulate flood risk based on water quality.

- Enhancing community involvement in low-carbon projects

- Poster: Perceptions of climate change and environmental law in the UK and France: A comparison. The poster is based on a small-scale survey conducted as part of an undergraduate internship and was presented at the WISERD conference in 2023. It raises interesting questions about the changes in environmental law following Brexit by comparison with France as an EU member. Accessible version of poster contents here